Archived - Impact Evaluation of Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements

Archived information

This Web page has been archived on the Web. Archived information is provided for reference, research or record keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Date: February 17, 2009

PDF Version (486 Kb, 75 pages)

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Approach

- 3. Profile of Four Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements

- 4. Evaluation Findings - Impact of Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements

- 5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix A: Land and Resource Management Bodies

Executive Summary

Comprehensive land claims are based on the assertion of continuing Aboriginal rights and claims to land that have not been dealt with by treaty or other means. Comprehensive land claim agreements (CLCAs) are modern treaties between Aboriginal claimant groups, Canada and the relevant province or territory. To date, a total of 21 comprehensive claim agreements, covering roughly 40% of Canada's land mass, have been ratified and brought into effect since the announcement of the Government of Canada's claims policy in 1973. These agreements involve over 91 Aboriginal communities with over 70,000 members.

The purpose of the evaluation is to assess the impacts of comprehensive land claim agreements and the extent to which the objectives established for the CLCAs have been achieved. Four agreements were examined: Northeastern Quebec Agreement with the Naskapi (NEQA); Inuvialuit Final Agreement (IFA); Gwich'in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (GCLCA); and Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (SDMLCA).

The methodology employed for the evaluation includes a literature review, key informant interviews, a comparative analysis of community-well being measures, administrative file review, and a survey of members of land and resource management and environmental review boards. Field work for the evaluation was conducted throughout the year 2008.

Key findings from the evaluation are as follows:

Fulfillment of CLCA Terms

The four land claim agreements were all centred on recognizing and clarifying the rights to land of the Aboriginal signatories, and the designation of larger areas of land as being within the settlement area and affording the Aboriginal signatories special access and land and resource rights within those lands. Each agreement included the transfer of funds from the federal government to the Aboriginal signatories. The agreements all prescribed the establishment of governance, administrative and financial bodies by the Aboriginal signatories and the creation of new land and resource co-management boards, as well as committees to manage land and resources in the settlement areas and manage the implementation of the agreements. The evaluation examined the extent to which these essential elements of the agreements have been fulfilled. Results from the evaluation conclude that:

- The terms of agreements have been fulfilled with respect to the transfer of funds and recognition of rights to land, but issues remain regarding the level of ongoing funding and the nature of federal responsibilities related to the implementation bodies prescribed by the agreements.

- The prescribed land and resource management boards and committees have been established in a timely fashion and are widely viewed as operating well, though some settlement areas have experienced difficulty at times in retaining board and committee members as well as maintaining an adequate level of capacity among members. The decentralized nature of some boards especially in the Sahtu and Gwich'in areas means that expertise and expenses are not easily shared among boards. Attracting and keeping highly skilled personnel (engineers, managers, resource and environmental expertise) will likely be an ongoing struggle in very small and remote communities.

- There is a perception among Aboriginal officials that the federal government is primarily interested in addressing the letter of the agreements and not the true spirit and intent, resulting in barriers to progress. From this perspective the objectives of the agreements have not yet been reached, though funds have been transferred, rights to land recognized and bodies established as agreed.

Clarity and Certainty of Ownership and Access to Land and Resources

One of the primary impetuses for the negotiation of the land claims agreements was the desire to establish an environment that was more conducive to resource development and other economic development opportunities, while protecting the interests of the Aboriginal people making claim to the settlement areas. Key to this was a greater degree of clarity and certainty as to the ownership of land and access to land and resources. An environment of greater certainty as to ownership and access was intended to reduce the risk associated with legal challenges and facilitate investment. Results from the evaluation conclude that:

- The land claim agreements have succeeded, with minor exceptions, in establishing clarity and certainty regarding land ownership and access.

- There have been several lawsuits filed in the JBNQA and NEQA settlement regions by non-beneficiaries, but no other legal challenges associated with land ownership and access or resource-related rights.

- Formal dispute resolution bodies have rarely been used to settle land ownership and access issues and there have been few informal disputes.

- Three issues related to land use that arose early on in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region have been settled after lengthy delays.

- Information on land ownership and access is readily available and industry has been informing itself and responding positively to the new circumstances, however, there remains some lack of clarity with regard to ownership and access among residents in the NWT settlement areas.

Enhancement of Working Relations among Stakeholders

The CLCAs are designed to improve working relations between the federal government and Aboriginal people as well as clarify and nurture a positive working relationship between Aboriginal groups and prospective developers from outside the settlement areas. Results from the evaluation conclude that:

- Aboriginal-to-industry relationships have changed fundamentally as a result of the CLCAs and are viewed positively by both Aboriginal and outside business representatives.

- Aboriginal-to-government relationships remain similar to before the land claim agreements despite limited improvements in certain areas.

- There has been an emergence of joint ventures and other close working relationships between Aboriginal companies and non-Aboriginal resource development companies.

- Aboriginal and government members of land and resource management bodies are working together collaboratively and effectively.

- The organizations and structures established under the agreements have altered internal Aboriginal political dynamics and highlighted the challenge of maintaining community-level decision making while gaining benefit from central structures and authorities.

Stable, Predictable Environment for Economic Development

The land claim agreements make reference to the objectives of achieving greater Aboriginal economic self-sufficiency and enabling Aboriginal people to participate fully in the northern Canadian economy. The focus of the evaluation is on the extent to which the CLCAs have contributed to creating an environment that encourages economic development. Results from the evaluation conclude that:

- The regulatory regime, in most instances, has been operating in a timely fashion and has not been a deterrent to resource development and investment.

- Land claim agreements have been an important factor in the increase in Aboriginal participation in the economy by contributing to the development of Aboriginal infrastructure and to both communally-owned and independent Aboriginal business development.

- There remains a challenge to improve training and business opportunities in the northern economy. A perception among Aboriginal leaders is that the lack of dedicated federal government economic development support, beyond programs of general application, is limiting progress.

Meaningful and Effective Voice for Aboriginal People in Decision-making

The four land claim agreements have provisions designed specifically to provide Aboriginal signatories with a stronger voice in decision-making with regard to land and resources. This was accomplished primarily through the land and resource management bodies established under the agreements. Results from the evaluation conclude that:

- The land and resource management regime represents a positive change in the role of Aboriginal people in the decision-making for the settlement areas. Aboriginal people now have input into development decisions affecting their communities.

- The land and resource management bodies have all been established with full and active participation from Aboriginal members. However, delays in nominations and appointments have hindered some activities.

- There is requirement to streamline the community consultation process as well as to support land and resource management bodies in managing their workloads and the technical aspects of development proposals.

- Land and resource management bodies are successful in balancing scientific and traditional knowledge in decision-making.

Social and Cultural Well-being in Aboriginal Communities

The preservation of cultural distinctiveness and identity is of paramount importance within Aboriginal communities and is evident in most agreements. The Comprehensive Land Claims Policy explicitly recognizes the goal to encourage cultural and social well-being through land claim agreements. The evaluation examines the extent to which the agreements have contributed to sustainable social and cultural well-being. Results from the evaluation conclude that:

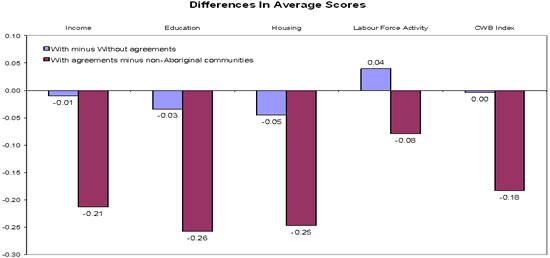

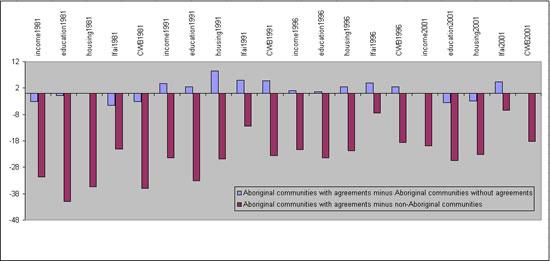

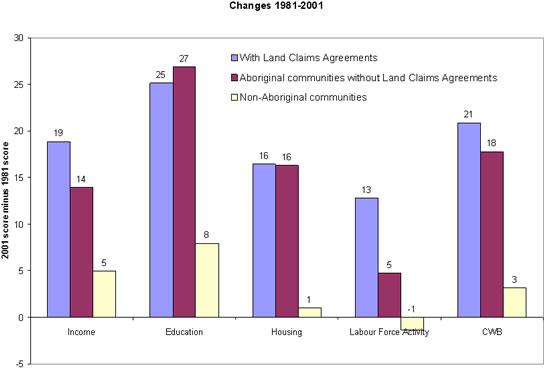

- There have been modest gains in employment, income, education and housing in settlement areas since the agreements have been in place.

- A comparison of "agreement" and "non-agreement" Aboriginal communities of similar size and location does not associate gains in well-being in the land claim communities with the land claim agreements themselves.

- Participation rates in traditional Aboriginal pursuits are lower than prior to the land claim agreements, yet are still prevalent.

- Knowledge of Aboriginal languages is on a decline. Programs using land claim agreement funding and other federal and provincial/territorial government support are working with the intention of reversing the trend.

- Crime and substance abuse rates are on the rise in the NWT. There is no evidence of a direct link to the land claim agreements, but many community residents see the agreements as forces of modernization which contribute to social problems.

In Conclusion:

- The federal government has fulfilled the terms of the comprehensive land claim agreements with respect to the transfer of funds and the recognition of rights to land to the Aboriginal signatories. Moreover, as prescribed under the agreements, the governance, administrative and financial bodies as well as the land and resource co-management boards and committees have been established.

- Comprehensive land claim agreements have created certainty and clarity regarding land ownership and use of land and resources. This has reduced the risk associated with legal challenges and created an environment that has facilitated investment.

- The land and resource management and regulatory regime established under the comprehensive land claim agreements have resulted in a collaborative and consensus-based decision-making process that is providing Aboriginal people with a meaningful voice on issues affecting their lands and resources.

- The comprehensive land claim agreements have been an important contributor in transforming the role of Aboriginal people in the economy by contributing to the development of Aboriginal infrastructure and Aboriginal business development. This has resulted in communities being well-positioned to take advantage of resource and other economic development opportunities.

- There have been modest gains in measures of income, employment, education and housing in the settlement areas since the agreements have been put in place though the evaluation was unable to determine whether the gains in well-being were directly linked to the land claims agreements.

- There has been insufficient recognition by the federal government of the costs and organizational and training requirements associated with the consultative approach and the land and resource management structures established under the agreements.

- There has been a lack of targeted, northern-appropriate federal economic development support that addresses the need to train and educate residents, develops strategies to retain those currently employed, and identifies business opportunities in remote communities.

- There is a perception among Aboriginal officials that the federal government has been primarily interested in addressing the letter of the agreements and not the true spirit and intent, resulting in barriers to progress. From this perspective the objectives of the agreements have not yet been reached, though funds have been transferred, rights to land recognized and bodies established as agreed. Differences in interpretation of objective provisions have meant that the anticipated change in relationship between the federal government and Aboriginal signatories towards greater collaboration and trust has not been realized.

It is recommended that INAC:

- In partnership with Aboriginal organizations and other federal departments and agencies, consider leading the establishment of a policy for the implementation of comprehensive land claims which would clarify roles and responsibilities and the federal approach to implementing CLCAs.

- Work with central agencies and other federal departments and agencies to establish a senior-level working group charged with overseeing issues that may arise in agreement implementation.

- Work in partnership with Aboriginal and provincial/territorial signatories to set specific objectives, establish targets, monitor progress and take remedial action as required to properly implement agreements.

- Work with land and resource management boards to streamline and strengthen consultative processes and identify training and administrative needs.

- Promote training and business development tailored to northern needs and circumstances, taking into account the high cost of delivering programs in the North.

1. Introduction

Comprehensive land claims are based on the assertion of continuing Aboriginal rights and claims to land that have not been dealt with by treaty or other means. Comprehensive land claim agreements (CLCAs) are modern treaties between Aboriginal claimant groups, Canada and the relevant province or territory. CLCAs define a wide range of rights and benefits to be exercised by claimant groups and usually include full ownership of certain lands in the area covered by the settlement; guaranteed wildlife harvesting rights; guaranteed participation in land, water, wildlife and environmental management throughout the settlement area; financial compensation; resource revenue-sharing; specific measures to stimulate economic development; and a role in the management of heritage resources and parks in the settlement area. Many agreements include provisions relating to Aboriginal self-government.

The purpose of this evaluation is to assess the impacts of comprehensive land claim agreements and the extent to which the objectives established for the CLCAs have been achieved.

1.1 Comprehensive Land Claims Policy

A Government of Canada policy for the settlement of Aboriginal land claims was established in 1973 following the Supreme Court of Canada ruling in the Calder case, involving the Nisga'a claim over title to their traditional lands in British Columbia. The introduction of In All Fairness: A Native Claims Policy, now the Comprehensive Land Claim Policy, was designed to lay out the principles to negotiate modern treaties originally put forth in the 1973 Indian and Northern Affairs (INAC) policy statement.

The objective of the policy was to provide a substantive and balanced negotiating process that would produce a long-lasting definition of rights to lands and resources. The original policy, which was reaffirmed in 1981, exchanged claims to undefined Aboriginal rights for a clearly defined package of rights and benefits set out in a settlement agreement. Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 recognizes and affirms Aboriginal and treaty rights that now exist or that may be acquired by way of land claim agreements.

Significant amendments to the Comprehensive Land Claims Policy were announced in December 1986. These included widening the scope of comprehensive claims negotiations to include offshore wildlife harvesting rights, sharing of resource revenues, an Aboriginal voice in environmental decision-making and a commitment to negotiate self-government. The amended policy also included a requirement to negotiate implementation plans with all claim agreements. The 1986 policy also allowed for the inclusion of provincial and territorial governments as partners at the negotiation table, as well as allowing for the protection of third party rights. In addition, two new terms "clarity and certainty" were inserted in the revised policy.

1.2 Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements

The first settled land claim was the James Bay Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) with the Cree and Inuit of northern Quebec in 1975. To date, a total of 21 comprehensive claim agreements, covering roughly 40% of Canada's land mass, have been ratified and brought into effect since the announcement of the Government of Canada's claims policy in 1973. These agreements involve over 91 Aboriginal communities with over 70,000 members. Most agreements were signed in the mid- to late-1990s, and the most recent, the Nunavik Inuit Land Claim Agreement, was signed in 2008. Outstanding claims cover approximately 20% of Canada involving 270 Aboriginal communities with approximately 200,000 members.

In addition to its lead role in negotiations, INAC has been delegated to coordinate and oversee the implementation of federal obligations which include monitoring other federal departments, such as Fisheries and Oceans, the Canadian Wildlife Service, Parks Canada, Industry Canada, Transport Canada, Environment Canada and Natural Resources Canada, as well as fulfilling its one-time and ongoing obligations as per the terms of the agreement. Departments and agencies must ensure that their policies, programs, statutes and regulations and on the ground activities comply with the land claim agreements.

Aboriginal signatories and the land and resource management bodies established under the agreements work regularly with federal departments and agencies in conducting research, developing management strategies, making decisions, seeking to ensure enforcement of those decisions and generally monitoring compliance in the settlement areas.

Provincial and territorial governments, as co-signatories to the agreements and/or implementation plans, are responsible to ensure that obligations within their jurisdiction are implemented in a timely manner and that laws, policies, programs and activities within the settlement areas are in accordance with the agreements.

The approach for evaluating CLCAs embraces the notion that parties to an agreement have high-level ideas about what they want to see achieved through the settlement and implementation of agreements. The following anticipated achievements represent a blending of information from Canada's Comprehensive Land Claims Policy, the preambles and individual chapters of the agreement and side agreements and interview results. The following issues express the various shared interests of the parties who signed the agreements:

- create certainty and clarity regarding ownership and use of lands and resources;

- provide for the participation of Aboriginal groups in decision-making concerning the use, management and conservation of wildlife, land, water, and other resources;

- create the conditions that support the emergence of new Aboriginal governance structures and relationships among federal, provincial and Aboriginal regional/local governments;

- create a stable environment for investment in the settlement area for the benefit of both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people;

- provide the tools for the continuation of an economic and spiritual relationship between Aboriginal people and the land;

- encourage and promote self-sufficiency and cultural and social well-being for Aboriginal people;

- provide Aboriginal communities with the tools to be meaningful participants in the general economy; and

- provide for the recognition of Aboriginal cultural values and traditions within Canadian society at large.

1.3 Recent Reports

Recent reports related to comprehensive land claims include:

- The Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples study on the implementation of comprehensive land claim agreements in Canada, which concluded that the current federal policy and organizational structures are ill-suited to manage the implementation of modern treaties and the complex issues that arise from these agreements.[Note 1]

- The review of the regulatory system across the North which concluded that the current system in the Northwest Territories (NWT) is overly complex and not sustainable in its current form given local capacities and the technical and workload demands it places on local advisory and regulatory bodies.[Note 2]

- The Auditor General of Canada's report on the Inuvialuit Final Agreement that found that INAC had not met some of its significant obligations and management responsibilities in implementing federal obligations under the Agreement.[Note 3]

- Report from the Institute for Research and Public Policy (IRPP) regarding Aboriginal quality of life under a modern treaty from the experiences of the Cree of James Bay and Inuit of Quebec.[Note 4]

2. Evaluation Approach

2.1 Evaluative Requirements

In 1998, a report of the Auditor General of Canada recommended that INAC "perform periodic evaluations of settlement implementation on a timely basis."[Note 5] The following year, the Public Accounts Committee recommended that INAC develop an evaluation framework and multi-year plan for land claim evaluations. In 2002, a framework for the evaluation of CLCAs was developed based on extensive consultation. In September 2004, the Treasury Board directed the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development to return with a schedule for the outcome evaluation of all CLCAs that have been in effect for at least 10 years. In 2006 a multi-year evaluation plan was prepared by the Departmental Audit and Evaluation Branch.[Note 6]

This impact evaluation will meet the commitments made to the Auditor General, the Public Accounts Committee and the Treasury Board, as well as support 2010 authority renewal requirements.

2.2 Scope and Timing

CLCAs that were considered for the evaluation had to have at least ten years of implementation experience and not to be in renewal negotiations. The evaluation therefore includes the following four agreements[Note 7]:

- Northeastern Quebec Agreement with the Naskapi (NEQA)

- Inuvialuit Final Agreement (IFA)

- Gwich'in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (GCLCA)

- Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (SDMLCA).

An evaluation assessment was completed in 2007 that identified the anticipated results of the agreements, the issues to be addressed, the indicators to be used to assess progress and the available sources of information. The terms of reference for the evaluation were approved by the Audit and Evaluation Committee in September 2007 with field-work being conducted throughout 2008. An internal INAC steering committee, with input from a separate advisory committee which included Aboriginal signatories, led to a refocusing of the original eight anticipated achievements to the six key issues to be covered by the evaluation.

2.3 Evaluation Issues

The evaluation addresses six broad issue areas that correspond to the anticipated outcomes of the agreements.

- Fulfillment of CLCA terms

- Clarity and certainty of ownership and access to land and resources

- Enhancement of working relations among stakeholders

- Stable, predictable environment for economic development

- Meaningful and effective voice for Aboriginal people in decision-making

- Social and cultural well-being in Aboriginal communities

2.4 Methodology

Literature Review

Based on literature from both the private and public sectors, the review was organized into five substantive sections: co-management of environment; land and resources; economic development; promoting self-sufficiency, cultural and social well-being; and, governance and inter-governmental relations.

Development of CLCA profiles

Detailed profiles were developed of the four comprehensive land claim agreements under study and include the ancestry and history of the people in the settlement areas, provisions of the agreements, approaches to implementation and the bodies established to accomplish implementation, as well as key issues that arose in the early years of implementation.

Data Analysis

INAC Comparative Analysis of Community Well-being Measures: INAC's Research and Analysis Directorate has developed measures of well-being in Aboriginal communities which will enable evaluators to assess changes in certain attributes from the years 1981 to 2001, including communities covered by the four CLCAs.[Note 8] This research element involved three types of analysis:

- Analysis of changes in the individual measures and overall community well-being within individual communities and for settlement areas as a whole, from the years 1981 through 2001;

- Comparative analysis of the target communities against the same measures in Aboriginal communities of a similar size and circumstance, in which comprehensive land claim agreements are not in place; and

- Comparative analysis of the target communities against the same measures in non-Aboriginal communities of a similar size and circumstance.

Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT) Bureau of Statistics data: Compilation and analysis of GNWT Bureau of Statistics data on a range of subjects including participation in traditional Aboriginal pursuits, knowledge levels of local Aboriginal languages, crime rates and substance abuse rates.

Document/administrative data review

Document and administrative data review included:

- Board and Committee annual reports;

- Data from resource management boards related to applications for land use permits and water licenses and subsequent rulings;

- Data from GNWT and Aboriginal organizations regarding Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal businesses operating in the settlement areas, including joint ventures;

- Annual reports and other reports of Aboriginal political and economic development as well as investment organizations; and

- Reports and descriptive documents from federal government departments, the Quebec government, GNWT and Aboriginal organizations relating to a range of topics including economic development, training and education programs, language and cultural programs, and social services and programs.

Survey of members of land and resource management, environmental review boards

The survey obtained the views of Aboriginal and government land and resource management board members regarding the operations of the boards in relation to the efficiency of licensing and permit processes, the extent to which Aboriginal perspectives are taken into account in board decisions, whether they believe a fair balance is being struck between economic, environmental and resource management interests and the extent and nature of collaboration between Aboriginal and government members.

The survey was conducted in the fall of 2008 and was distributed to 61 board members from 11 different boards. A response rate of 52% was achieved with the responses well distributed across the participating bodies and included responses from all participating boards/committees.Community meetings

Community meetings were held in Kawawachikamacha for the Naskapi agreement and in Inuvik, Aklavik and Paulutuk for the Inuvialuit agreement. As the meetings were not successful in attracting a sufficient number to represent residents' views on the land claims, they were not continued for the Gwich'in and the Sahtu Dene and Métis agreements, rather the number of key informants were expanded to include community members such as elders, teachers, and social service workers.

Key informant interviews

A total of 216 key informant interviews were conducted with the vast majority taking place on-site.

- INAC Headquarters (28 interviews) - Sectors: Treaties and Aboriginal Government; Policy and Strategic Direction; Northern Affairs; Lands and Economic Development; Regional Operations

- INAC Regions (10 interviews) – Regions: Quebec and NWT

- Other Government Departments and Agencies (16 interviews): Fisheries and Oceans Canada; Environment Canada; Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency; Parks Canada; Natural Resources Canada; Justice Canada; Public Works and Government Services Canada; Transport Canada; Canada Economic Development for the Quebec Regions; Health Canada; Canadian Heritage; Human Resources and Skills Development Canada; and Industry Canada

- Government of Quebec (5 interviews): Secrétariat aux affaires autochtones

- Government of the Northwest Territories (5 interviews): Aboriginal Affairs and Intergovernmental Relations; Office of Devolution; GNWT Bureau of Statistics, Education, Culture and Employment; Aurora College[Note 9]

- Government of Yukon (2 interviews): Environment Yukon; Executive Council Office

- Aboriginal Group Leadership and Community Members (132 interviews):

| Agreement | Political Leaders/staff | Board members/staff | Elders | Other[Note 10] | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naskapi | 7 | 2 | 2 | 17 | 28 |

| Sahtu | 17 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 34 |

| Gwich'in | 14 | 10 | 3 | 7 | 34 |

| Inuvialuit | 11 | 5 | 4 | 16 | 36 |

| Total | 49 | 24 | 12 | 47 | 132 |

- Industry (18 interviews): Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers; Mining Association of Canada; Canadian Gas Association; Small Explorers and Producers Association of Canada; NWT Chamber of Mines; selected Quebec firms; and, selected NWT firms

2.5 Limitations

The evaluation was limited in its ability to assess the impacts of the land claim agreements due to the following:

- Limited baseline data: There was little in the way of baseline data available to use to compare with current measures of progress. Current data and inferences are drawn for comparison purposes and are based on interviews with knowledgeable local residents regarding the circumstances at the time of the agreements.

- Reliance on key informant interviews as source of data: To the greatest extent possible, findings from the evaluation are based on multiple sources of evidence and interview findings that are analysed in conjunction with other lines of evidence. There are areas in which the evaluators could not obtain additional data; hence the evaluation finding is derived solely from key informant interviews. The report will identify when a finding is based solely on the opinions expressed by key informants.

- Accuracy of Census data in remote locations: There is a commonly held view among Aboriginal leaders in the settlement areas that the data in the more remote communities may be inaccurate due to the lack of participation in the Census. This view is not shared by officials at Statistics Canada or by research officials within the department.

- Limited analysis of social well-being: It was recognized that in selecting the Comparative Analysis of Community Well-being Measures as proxies for social health in the settlement areas, the evaluation was being restrictive in its application of measures. Due to scope and time constraints, this approach was agreed to by the steering committee prior to the evaluation being launched.

3. Profile of Four Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements

3.1 Northeastern Quebec Agreement with the Naskapi (NEQA)

Settlement area: 1,165,286 km2

Settlement lands: 326.8 km2 Category I Lands (Naskapi-owned); 4,144.0 km2 Category II Lands (exclusive rights); 1 million km2 Category III Lands (rights shared with Cree and Inuit)

Date settled: NEQA (January 31, 1978); Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act (June 14, 1984); NEQA Implementation Agreement (September 13, 1990)

Population: (2007) 809 beneficiaries

Communities: Kawawachikamach

Financial settlement: Capital transfer of $9 million to be paid over a maximum of 12 ½ years depending on the size of annual revenue shares from Hydro Quebec; supplemental capital transfer of $1.7 million in 1990; an additional capital transfer of $0.9 million in 1997 for economic development.

Background to agreement

The James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement (JBNQA) was signed in 1975 by the governments of Canada and Quebec, the Crees and Inuit of Northern Quebec, the James Bay Energy Corporation, the James Bay Development Corporation and Hydro-Quebec. The Naskapi were former inhabitants of areas of land under the agreement and sought, but could not obtain, involvement in the JBNQA negotiations. The parties to the JBNQA recognized the legitimacy of the Naskapi claim and entered into negotiations which led to the signing of the Northeastern Quebec Agreement (NEQA) on January 31, 1978. This agreement made the Naskapi party to the major provisions of the JBNQA.

There was no implementation plan as part of the NEQA, however, the decision of the Iron Ore Company of Canada to close its mining operations in 1982 near Schefferville had profound implications for the implementation of the NEQA, particularly concerning the provisions dealing with health, social services, training and job creation. The change in circumstances in Schefferville prompted the Naskapi and the Government of Canada to undertake a joint evaluation of Canada's responsibilities under NEQA in the late 1980s. Those negotiations led to the signing of An Agreement Respecting the Implementation of the Northeastern Quebec Agreement on September 13, 1990.

Objectives of the agreement

No broad objectives were identified as a preamble to the NEQA as was the case for the other three agreements under study. Various sections of the agreement made reference to the purpose of specific measures.

Lands Recognized

The total NEQA settlement area is the same as that of the JBNQA - 1,165,286 km2. The Naskapi received 326.8 km2 of Category I lands and 4,144 km2 of Category II lands. The remaining 1,000,000 km2 are identified as Category III lands which are shared with the Inuit and Cree.

Rights Recognized

The Naskapi exchanged their claims, rights and territorial interests for other rights and benefits, as specified in the agreement. These included participation in an environmental and social protection regime; economic development; hunting, fishing and trapping rights; as well as the creation of regional public institutions under the jurisdiction of the Quebec government related to education and health services.

Naskapi hunting, fishing and trapping rights vary according to the category of land. Category I lands are for the exclusive use of the Naskapi, and also hold their primary residence of Kawawachikamach. Category II lands are under provincial jurisdiction, but the Naskapi have exclusive hunting, fishing and trapping rights and the power to participate in the management of hunting, fishing and trapping operations. Category III lands are shared with the Inuit and Crees and provide the Aboriginal groups the exclusive right to harvest certain aquatic species and fur-bearing mammals as well as to participate in the administration and development of this land area. The Quebec government, the James Bay Energy Corporation, Hydro-Quebec and the James Bay Development Corporation have specific rights to develop resources on Category III lands, subject to impact assessments by the federal and provincial governments.

The governments of Quebec and Canada both provide compensation funds to the Naskapi that are administered by the Naskapi Development Corporation to support economic development in Kawawachikamach.

Implementation

In 1984 the Parliament of Canada passed the Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act to implement the JBNQA and NEQA provisions for local government of communities. This Act provided for the setting up and operation of a Cree-Naskapi Land Registry as well as a Cree-Naskapi Commission. There was no implementation plan included in the original agreement, but in 1990 such an agreement was reached.

The 1990 NEQA Implementation Agreement detailed how Canada would discharge its responsibilities under the agreement by means of the following:

- Creating an Interdepartmental Committee to serve as a channel for communication between the various federal departments and the Naskapi entities involved in matters related to the NEQA;

- Establishing a dispute resolution mechanism;

- Providing capital, operations and maintenance funding; and

- Establishing a working group (Canada and Naskapi) to study ways and means of increasing Naskapi employment.

The JBNQA and NEQA provide for consultative bodies to consult with the provincial and federal governments. The Naskapi have two representatives on the Hunting, Fishing and Trapping Coordinating Committee. Representatives of the Kativik Regional Government, which has Naskapi members, sit on the Kativik Environmental Quality Commission, the Kativik Environmental Advisory Committee and the Federal Review Panel North. To date no Naskapi representative have sat on these bodies, in addition, the Naskapi Education Committee was set up to advise on the running of the school in Kawawachikamach, with 75% of the funding contributed by the government of Canada.

Self-government

No self-government provisions are included in the agreement.

Financials

The 1978 NEQA provided the Naskapi people with $9 million and treaty settlement lands, rights and benefits. The NEQA Implementation Agreement (signed September 13, 1990) gave the Naskapi a further one-time payment of $1,639,840.

The Naskapi continue to receive ongoing funding via a capital grant $1,448,400 (07/08) which is inflation adjusted in accordance with the approved growth applied to the Indian and Inuit programming portion of INAC's budget. The Naskapi Capital Funding Agreement is in effect from April 1, 2005 to March 31, 2010 and covers various capital projects in Kawawachkamach.

Naskapi also receive an ongoing O&M grant of $5,140,233 (07/08) which is population and Final Domestic Demand Implicit Price Index (FIDDIPI) adjusted. The Naskapi Operations and Maintenance Funding Transfer Payment Agreement is also in effect from April 1, 2005 to March 31, 2010. This agreement is for local government services provided by the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach.

3.2 Inuvialuit Final Agreement (IFA)

Settlement area: 13,000 km2 surface and sub-surface rights; 77,700 km2 surface rights

Settlement lands: 6 blocks of 1,800 km2 around each community; 2,070 km2 in Cape Bathurst area; surface title to 77,700 km2 of land

Date settled: June 5, 1984

Population: (2007) 3,812 participants[Note 11]

Communities: Aklavik, Holman, Inuvik, Paulatuk, Sachs Harbour and Tuktoyaktuk

Financial settlement: Capital transfer of $78 million (1984 $) in scheduled payments over 15 years starting in 1984; a one-time $10 million transfer in 1984 (economic enhancement fund); a one-time $7.5 million transfer in 1984 (social development fund).

Background to the agreement

In the Yukon and Northwest Territories, lands and non-renewable resources fall under federal jurisdiction, however, territorial governments have jurisdiction over some renewable resources and participate fully in the negotiations and the application of the land claims policy.

The Inuvialuit had never signed a treaty with Canada though in the 1970s, the Inuvialuit did establish an organization called the Committee for Original People's Entitlement (COPE) in order to have a collective voice in deciding their future. The Inuvialuit, through COPE, made a formal request to the Government of Canada for land claim and self-government negotiations. The Inuvialuit claim was accepted for negotiation on May 13, 1976. The Government of Canada and COPE signed the Inuvialuit Final Agreement (IFA) on June 5, 1984. It was the first comprehensive land claim agreement signed north of the 60th parallel and the first outside Quebec.

Objectives of the agreement

The basic goals expressed by the Inuvialuit and recognized by Canada in concluding the agreement are:

- To preserve Inuvialuit cultural identity and values within a changing northern society;

- To enable Inuvialuit to be equal and meaningful participants in the northern and national economy and society; and

- To protect and preserve the Arctic wildlife, environment and biological productivity.

As with all land claim agreements, there are other objectives established for certain specific measures.

Lands Recognized

The Inuvialuit were granted surface and subsurface title to 13,000 km2 of land: six blocks of 1,800 km2 around the communities of Aklavik, Holman, Inuvik, Paulatuk, Sachs Harbour and Tuktoyaktuk, as well as 2,070 km2 in the Cape Bathurst area. In addition, the Inuvialuit were granted surface title to 77,700 km2 of land selected throughout the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR). The Inuvialuit, through the Inuvialuit Land Corporation, hold title to these lands though they must honour existing rights such as leases. In cases where the Inuvialuit own the subsurface rights, they receive the proceeds from any resource development in those areas. The settlement lands do not include the actual sites of the communities, which vary in size from 3.9 to 13 km2.

Rights Recognized

The agreement gives the Inuvialuit certain rights and benefits in exchange for their agreement to extinguish their interests based upon traditional land use and occupancy. It includes wildlife harvesting rights, socio-economic initiatives and participation in wildlife and environmental management.

Implementation

The IFA did not include an implementation plan as it pre-dated the 1986 policy, which calls for implementation plans to accompany land claim agreements. In 1986 an implementation coordinating committee was established that included the Inuvialuit, Government of Canada, Government of Yukon and Government of the Northwest Territories. This committee functioned and produced annual reports until 1989 and then became inactive. In 1999 the same parties agreed to re-establish the IFA Implementation Coordinating Committee. The Committee continues to monitor the fulfilment of ongoing obligations of the parties which are contained in the agreement and produces annual reports.

As part of implementation, the agreement established various Inuvialuit corporations to manage finances, economic development and social and cultural matters on behalf of the Inuvialuit people, including:

- Inuvialuit Regional Corporation (IRC) – composed of six community corporations from the Inuvialuit communities of Aklavik, Holman, Inuvik, Paulatuk, Sachs Harbour and Tuktoyaktuk;

- Inuvialuit Land Corporation and Inuvialuit Land Administration;

- Inuvialuit Investment Corporation, Inuvialuit Development Corporation, Inuvialuit Petroleum Corporation; and

- Inuvialuit Game Council.

Self-government agreements

A self-government process began in 1993 with the establishment of an agreement between the Inuvialuit and Gwich'in to negotiate a regional public government for the Beaufort Delta Region. By March, 2005, the Gwich'in Tribal Council decided not to participate in the process though the Inuvialuit continued negotiations with the federal government. On May 30, 2007, the Government of Canada, the Government of the Northwest Territories and the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation signed the Inuvialuit Self-Government Process and Schedule Agreement as a basis for carrying on negotiations under the existing Agreement-in-Principle, which was negotiated jointly with the Gwich'in. This process is intended to work toward a final agreement that respects section 4(3) of the IFA to implement the inherent right of self-government for the Inuvialuit.

Financial terms

Under the financial terms of the agreement, the Inuvialuit received a tax-free capital transfer of $78 million (in 1984 dollars) which was payable over 14 years. They also received a one-time payment of $10 million toward an economic enhancement fund and $7.5 million to a social development fund. Canada set off against the initial amount of capital transfer payable to the Inuvialuit Development Corporation the amounts of the interest free loans owing by the Corporation to repay a little over $9.6 million in negotiation loans advanced by Canada since the execution of the Agreement-in Principle.

While the IFA, unlike more recent land claim agreements, does not have an implementation plan, the two parties to the claim - Canada and the Inuvialuit - as well as the Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT) and Yukon Government, have agreed to a general list of implementation tasks that will be funded by the federal government. Funding for the implementation of the IFA has been renewed every five years since 1994 when current funding levels were established. Every year the base amount is multiplied by the FDDIPI number that is allocated for April 1st. In 2007-08 the Inuvialuit received $1,907,861.00.

3.3 Gwich'in Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (GCLCA)

Settlement area: 57,000 km2 in the Mackenzie Delta Region of the NWT and 1,554 km2 in the Yukon

Settlement lands: Total of 22,422 km2: 16,264 km2 fee simple land, 6,065 km2 land with mineral and surface rights; 93 km2 only mineral rights

Date settled: April 22, 1992

Population: (2007) 2,500 beneficiaries

Communities: Aklavik, Fort McPherson, Inuvik and Tsiigetchic

Financial settlement: Capital transfer of $75 million to be paid over 15 years starting in 1992. Annual share of resource royalties from development in the settlement area equal to 7.5% of the first $2 million received by the federal government that year, and 1.5% of any additional royalties; a one-time training fund of $761,000.

Background to the agreement

The Gwich'in Comprehensive Land Claim began as an integral part of the Dene/Métis Comprehensive Land Claim, involving the entire Mackenzie Valley south of the coastal Inuvialuit area. Though a final agreement had been initialled by the parties in April 1990, the joint Dene/Métis assembly had called for the renegotiation of fundamental elements of the agreement prior to the final agreement being signed. This renegotiation was not supported by the Mackenzie Delta Tribal Council or the representatives of the Sahtu Dene and Métis. Canada would not agree to renegotiate the initialled agreement and discontinued the Dene/Métis claim. Prompted by the request of both the Mackenzie Delta Tribal Council (the Gwich'in) and the Sahtu Tribal Council for regional claim settlements, Canada had agreed to negotiate towards a regional settlement of the claim on the basis of the April 1990 agreement, with any of the five Dene/Métis regions who had requested one.

In August 1990, the Gwich'in of the Delta region withdrew their negotiating mandate from the Dene/Métis leadership and requested Canada to negotiate a regional settlement on the basis of the April agreement. Negotiations with the Gwich'in began in November 1990 and the GCLCA was ratified by the Gwich'in in September 1991 and was approved by the federal government and the Government of the Northwest Territories in March 1992.

Objectives of the agreement

The GCLCA has the following broad objectives as set out in the first section of the agreement:

- To provide for certainty and clarity of rights to ownership and use of land and resources;

- To provide the specific rights and benefits in the agreement in exchange for the relinquishment by the Gwich'in of certain rights claimed in any part of Canada by treaty or otherwise;

- To recognize and encourage the Gwich'in way of life which is based on the cultural and economic relationship between the Gwich'in and the land;

- To encourage the self-sufficiency of the Gwich'in and to enhance their ability to participate fully in all aspects of the economy;

- To provide the Gwich'in with specific benefits, including financial compensation, land and other economic benefits;

- To provide the Gwich'in with wildlife harvesting rights and the right to participate in decision making concerning wildlife harvesting and management;

- To provide the Gwich'in the right to participate in decision making concerning the use, management and conservation of land, water and resources;

- To protect and conserve the wildlife and environment of the settlement area for present and future generations; and

- To ensure the Gwich'in the opportunity to negotiate self-government agreements.

Other objectives have been identified in relation to specific measures in the agreement.

Lands Recognized

The agreement provides for a 57,000 km2 settlement area within the Mackenzie Delta Region of the NWT and a 1,554 km2 area within the Yukon which is not part of the settlement area. The agreement provides fee simple title, or private ownership, of the surface of 16,264 km2 of land, another 6,065 km2 that include mineral rights and 93 km2 of land with only mining and mineral rights, for a total of 22,422 km2 under Gwich'in title.

Rights Recognized

In their settlement area, the Gwich'in have extensive and detailed wildlife harvesting rights, guaranteed participation in decision-making structures to be established for the management of wildlife and the regulation of land, water and the environment, and rights of first refusal to a variety of commercial wildlife activities. They also receive a portion of annual resource royalties in the Mackenzie Valley.

The Gwich'in have exchanged certain rights established in Treaty 11 for defined land claim benefits. The hunting, fishing and trapping rights under the Treaty are relinquished within the settlement area, the Western Arctic Region, the treaty area east of the Western Arctic Region, and the Yukon where they are replaced by provisions of the land claim agreement. If Dene/Métis in other areas of the Mackenzie Valley settle their land claims, the Gwich'in will automatically surrender treaty harvesting rights in these areas. Treaty rights, which were not specifically given up in the agreement continue to exist and include annual treaty payments and education.

Implementation

The GCLCA was the first agreement signed since the federal government established its 1986 comprehensive claims policy, which required that final agreements be accompanied by implementation plans. The GCLCA provides for the creation of an Implementation Committee, consisting of three senior officials that each represent the Government of Canada, the Government of the Northwest Territories and the Gwich'in Tribal Council. This committee operates on a consensus basis to provide direction and to monitor the status of the implementation plan while attempting to resolve any implementation disputes. The committee is also responsible for providing annual reports to the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs to conduct a general review of implementation in its fifth year and to conduct a broad review in preparation for negotiation of a follow-up implementation plan in its tenth year.[Note 12]

The agreement designates the Gwich'in Tribal Council as the primary Gwich'in organization with the authority to create designated bodies to manage finances, land administration, investments, economic development and social and cultural affairs. The Tribal Council remains the central Gwich'in body for implementing the agreement. The agreement establishes regulatory and advisory bodies at the regional and community levels in order to manage land and resource and environmental issues.

Self-government

The GCLCA provides for the process of negotiating self-government, which had begun with the 1993 agreement between the Inuvialuit and Gwich'in to work together to negotiate a regional public government for the Beaufort Delta Region. The resulting Agreement-in-Principle for self-government was signed in April 2003 by the Government of Canada, the Government of the Northwest Territories, the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation and the Gwich'in Tribal Council.

In March 2005, the Gwich'in Tribal Council decided not to participate in the joint process with the Inuvialuit and by the winter of 2006, had set up their own self-government team and had sent a formal letter to the Minister of INAC with a request to proceed with negotiations without the Inuvialuit. The Gwich'in self-government committee has continued to negotiate the structure of the self-government and community constitutions.

Financials

Under the financial terms of the agreement, the Gwich'in received a tax-free capital transfer of $75 million (1990 dollars) from the Government of Canada, which was paid annually over a 15-year period, as well as an annual share of resource royalties equal to 7.5% of the first $2 million received by the federal government that year and 1.5% of any additional royalties. The Gwich'in Tribal Council agreed to repay to Canada over $8 million in negotiation loans over 13 years and to pay 15% of the negotiation loans incurred by the Dene Nation and the Métis Association of the Northwest Territories between 1975 and November 7, 1990.

In 2003, a renewed implementation plan for the second ten-year implementation period was developed and finalized by the three parties to the Agreement. Every year the base amount is multiplied by the FDDIPI number that is allocated for April 1st. In 2007-08 the Gwich'in received $6,637,890.00.

3.4 Sahtu Dene and Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement (SDMLCA)

Settlement area: Sahtu Settlement Area is 280,238 km2 in the Mackenzie Valley and Great Bear Lake region of the Northwest Territories.

Settlement lands: Title is granted for 41,437 km2 of which 1,813 km2 includes subsurface rights.

Date settled: September 6, 1993

Population: (2007) 2,500 beneficiaries

Communities: Colville Lake, Deline, Fort Good Hope, Norman Wells and Tulita

Financial settlement: Capital transfer of $75 million to be paid over 15 years starting in 1993. Annual share of resource royalties from development in the settlement area equal to 7.5% of the first $2 million received by the federal government that year, and 1.5% of any additional royalties; a one-time training fund of $850,000.

Background to agreement

In September 1990, the Sahtu Dene and Métis withdrew their authorization for the Dene/Métis to represent them in the broad NWT agreement that had been negotiated, as with the Gwich'in, and requested a regional settlement. In July 1993, the Sahtu Dene and Métis approved the Sahtu Dene Métis Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement and after ratification, the agreement was approved by the Government of Canada and the Government of the Northwest Territories and was signed on September 6, 1993.

Objectives of the agreement

The SDMLCA has the following broad objectives as set out in the first section of the agreement:

- To provide for certainty and clarity of rights to ownership and use of land and resources;

- To provide the specific rights and benefits in the agreement in exchange for the relinquishment by the Sahtu Dene and Métis of certain rights claimed in any part of Canada by treaty or otherwise;

- To recognize and encourage the Sahtu Dene and Métis way of life which is based on the cultural and economic relationship between the Sahtu Dene and Métis and the land;

- To encourage the self-sufficiency of the Sahtu Dene and Métis and to enhance their ability to participate fully in all aspects of the economy;

- To provide the Sahtu Dene and Métis with specific benefits, including financial compensation, land and other economic benefits;

- To provide the Sahtu Dene and Métis with wildlife harvesting rights and the right to participate in decision making concerning wildlife harvesting and management;

- To provide the Sahtu Dene and Métis the right to participate in decision making concerning the use, management and conservation of land, water and resources;

- To protect and conserve the wildlife and environment of the settlement area for present and future generations; and

- To ensure the Sahtu Dene and Métis the opportunity to negotiate self-government agreements.

Other objectives are identified in relation to specific measures within the agreement.

Lands Recognized

The Sahtu Settlement Area (SSA) is 280,238 km2 in the Mackenzie Valley and Great Bear Lake region of the Northwest Territories. The agreement provides the Sahtu Dene and Métis with title to 41,437 km2 of land which includes 1,813 km2 of subsurface rights.

Rights Recognized

The Sahtu Dene and Métis have exchanged certain rights established in Treaty 11 for the rights spelled out in the agreement regarding wildlife harvesting. The agreement confirms hunting and fishing rights of the Sahtu Dene and Métis throughout the SSA and establishes their exclusive trapping rights. The Sahtu Dene and Métis are guaranteed participation in institutions of public government for renewable resource management, land use planning, and land and water use in the SSA as well as participation in environmental impact assessments and reviews in the Mackenzie Valley. Their participation is through membership on public government boards and through consultation.

Implementation

The Sahtu Dene and Métis Agreement provides for the creation of an Implementation Committee, consisting of three senior officials that each represent the Government of Canada, the Government of the Northwest Territories and the Sahtu Tribal Council. This committee operates on a consensus basis to provide direction and monitor the status of the implementation plan while attempting to resolve any implementation disputes. The committee is also responsible for providing annual reports to the Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs to conduct a general review of implementation at year five and to conduct a broad review in preparation for negotiation of a follow-up implementation plan at year 10.[Note 13]

The agreement designates the Sahtu Tribal Council as the primary Sahtu organization with the authority to create designated bodies to manage finances, land administration, investments, economic development and social and cultural affairs. The Sahtu subsequently established the Sahtu Secretariat Incorporated (SSI) as their main implementation body, governed by representatives of seven land corporations within their five communities with two of the communities having separate Métis land corporations in addition to the Sahtu corporations. The agreement establishes regulatory and advisory bodies at the regional and community levels that manage land and resource and environmental issues.

Self-government

The agreement provides for negotiation of self-government agreements to be brought into effect through federal and/or territorial legislation. The communities in the Sahtu area are at different stages of the negotiation process. The community of Deline was the first, in 1996, to pursue a self-government agreement and is close to concluding its agreement. The negotiations for a Norman Wells agreement began in the fall of 2005 and are nearing completion. Self-government negotiations for Tulita began in 2003 and a Final Agreement is expected to be completed before 2011. Fort Good Hope and Colville Lake have formally requested to begin self-government negotiations.

Financials

Under the financial terms of the agreement, the Sahtu received a tax-free capital transfer of $75 million (1990 dollars) from the Government of Canada, paid annually over a 15-year period, as well as an annual share of resource royalties equal to 7.5% of the first $2 million received by the federal government that year and 1.5% of any additional royalties. The Sahtu Tribal Council agreed to repay the Canadian Government over $10.8 million in negotiation loans, over 15 years, as well as to pay 15 % of the negotiation loans incurred by the Dene Nation and the Métis Association of the Northwest Territories between 1975 and November 7, 1990.

In 2004-05, after ten years of implementation activities, the implementation plan for the Sahtu Dene and Métis Agreement was renewed for a further 10 years. Every year the base amount is multiplied by FDDIPI number that is allocated for April 1st. In 2007-08, the Sahtu received $3,209,630.26to carry out their obligations in the agreement.

4. Evaluation Findings - Impact of Comprehensive Land Claim Agreements

The impacts of the four comprehensive land claim agreements under study are organized to correspond to the six issue areas.

- Fulfillment of CLCA terms

- Clarity and certainty of ownership and access to land and resources

- Enhancement of working relations among stakeholders

- Stable, predictable environment for economic development

- Meaningful and effective voice for Aboriginal people in decision-making

- Social and cultural well-being in Aboriginal communities

4.1 Fulfillment of CLCA Terms

The four land claim agreements were all centred on the recognition and clarification of rights to land to the Aboriginal signatories and the designation of larger areas of land as being within the settlement area and affording the Aboriginal signatories special access and land and resource rights within those lands. In addition, each agreement included the transfer of funds from the federal government to the Aboriginal signatories. The agreements all prescribed the establishment of governance, administrative and financial bodies by the Aboriginal signatories and the creation of new land and resource co-management boards, as well as committees to manage land and resources in the settlement areas and manage the implementation of the agreements.

The evaluation examined the extent to which these essential elements of the agreements have been fulfilled. Results from the evaluation conclude that:

- The terms of agreements have been fulfilled with respect to the transfer of funds and the recognition of rights to land, but issues remain regarding the level of ongoing funding and the nature of federal responsibilities related to the implementation bodies prescribed by the agreements.

- The prescribed land and resource management boards and committees have been established in a timely fashion and are widely viewed as operating well, though some settlement areas have experienced difficulty at times in retaining board and committee members as well as maintaining an adequate level of capacity among members. The decentralized nature of some boards especially in the Sahtu and Gwich'in areas means that expertise and expenses are not easily shared among boards. Attracting and keeping highly skilled personnel (engineers, managers, resource and environmental expertise) will likely be an ongoing struggle in very small and remote communities.

- There is a perception among Aboriginal officials that the federal government is primarily interested in addressing the letter of the agreements and not the true spirit and intent, resulting in barriers to progress. From this perspective the objectives of the agreements have not yet been reached, though funds have been transferred, rights to land recognized and bodies established as agreed.

Funds transferred

Land claim agreements include capital payment schedules which are negotiated as part of the overall negotiations leading to settlement. The Government of Canada transfers the capital funds under a statutory grant regime according to each agreement's schedule. No concerns were identified regarding the payment process, including timeliness, from the perspectives of the federal government or Aboriginal organization recipients. The Auditor General confirmed this finding, in the Inuvialuit context, in her 2007 October report.[Note 14] Based on interviews with Aboriginal representatives, it is clear that the same conclusion applies to all four agreements which are being evaluated.

While this evaluation does not focus on implementation issues, concerns were raised regarding the level of ongoing implementation funding. Concerns were raised primarily regarding INAC's funding of land and resource management boards established under the agreements but also with funding from other departments and agencies for research and for the operations of certain implementation bodies in the Inuvialuit region. As funding is re-negotiated every several years, there have been concerns noted by Aboriginal signatories and echoed by the Auditor General of Canada about the lack of clarity over what specific obligations the federal government has under the agreements and implementation plans and the lack of clarity over which departments or agencies have responsibilities for and systematic ways to ensure that obligations are being met.[Note 15] More recently, there is concern that implementation funding is not sufficient to allow board budgets to keep up with inflation and rising costs, especially rising fuel costs and the costs associated with substantial and unpredicted increases in the numbers of development applications which require action from the boards.

From INAC's perspective this issue is addressed through the implementation plan renewal process which takes place in 10 year intervals. In addition to renewals, there are established processes within each agreement where the parties can access additional funding should the need arise, and these processes have been triggered successfully numerous times. However, the evaluation found that most federal and territorial governments and Aboriginal officials interviewed for the evaluation do not believe funding levels are adequate to enable most boards to function as fully as intended.

Although the amount of implementation funding may be in dispute in some cases, particularly in the NWT settlement areas, there have been improvements in the process whereby the funds are transferred. Historically, the process of transferring funds to Aboriginal groups, the Government of the Northwest Territories and the various boards was inefficient, according to Aboriginal and GNWT officials, due to federal budget cycles and Treasury Board policies which limited the boards' abilities to carry funds over from one year to the next. In the late 1990s, INAC began using a special contribution payment, whereby the recipient bodies could carry over funds after March 31st each year. This was a significant improvement for Aboriginal groups and boards because it allows them to properly plan for activities without the constraints of the federal budgetary cycle. All funding recipients must provide INAC with work plans and regular reports regarding the use of implementation funds. In accordance with Treasury Board Policy on Transfer Payments, INAC does not flow the money until agreements and reports are in place and agreed on. However, the ability of boards to meet these requirements varies, which can prove problematic in terms of cash flow. INAC works closely with the boards to assist in meeting work plan and reporting requirements but board capacity and staffing issues can hamper the process.

Land title

Land title transfers are completed according to the terms of individual agreements. Respondents representing Aboriginal organizations and governments indicated that the Registrars of Land Titles have worked effectively in formally transferring lands in all four claim areas. However, surveys required for land transfers have sometimes been delayed resulting in delays of land transfers. Surveys regarding settlement lands are the responsibility of Natural Resources Canada (NRCan). These delays have not appeared to result in disputes, although they have caused frustration for Aboriginal groups in the NWT and for the Naskapi in Northeastern Quebec.

Among the four agreements covered in this evaluation, the Inuvialuit Final Agreement (IFA) is the single case involving more serious complications, as indicated in documents reviewed for the evaluation and in the Auditor General's October 2007 report,[Note 16] and as acknowledged by INAC and GNWT officials. The IFA includes clauses obliging the federal Crown to exchange lands with the Inuvialuit to offset certain lands the Crown wanted to maintain within the settlement area for various purposes, as well, the Crown is obliged to return parcels of land that it maintains once those lands are no longer needed (e.g., National Defence sites for the Distant Early Warning System). The Auditor General found that, of 20 parcels being used by the Crown at the time of the agreement, 13 were subsequently no longer needed by the Crown. Despite requests from the Inuvialuit, none of these parcels were returned until 2008, reportedly due to delays by NRCan in surveying the affected parcels. These disputed parcels represent less than 1% of total IFA land. There are no remaining disputed parcels of land.

Land and resource management boards and committees established

Respondents generally view the establishment of land and resource management boards and committees as a positive result of land claim settlements. However, there have been instances where the enabling federal or territorial legislation was not in place to allow the establishment of a board. The Surface Rights Boards have not been put in place in the Gwich'in and the Sahtu regions due to the absence of relevant legislation. To date, this absence has not been problematic. There is however variation among claimant groups in terms of the overall effectiveness and ability to maintain full membership on the various boards and committees.

Typically the nomination of board members is shared between INAC, the territorial/provincial government and the Aboriginal body with overarching responsibility. For some groups, notably the Gwich'in and Sahtu, the timeliness in appointments by the Minister for their nominations has reportedly been problematic and in some cases the Aboriginal parties have been slow to nominate new members. According to INAC and Aboriginal officials, the Gwich'in and the Sahtu occasionally face difficulty finding suitable individuals to nominate for membership on boards/committees. This problem is exacerbated by a high rate of turnover among board and committee members.

The lack of adequate funding, particularly core funding, is often cited as a major problem, most notably by Aboriginal respondents although government officials also acknowledged the issue. Lack of funding is seen as a reason for the inability of boards and committees to do the training and development work required to raise their members to higher skill levels. Inadequate funding is also seen to apply to staff shortages, including administrative and research staff, for boards/committees.

While problems limiting the full operation of the boards and committees were identified, most respondents cited the establishment of boards and committees as one of the more important successes of the comprehensive land claims process. The one exception is the NEQA, where the Naskapi consider that while the boards were established as intended, the make-up of the boards leaves them under-represented and therefore unable to adequately protect their interests.

Aboriginal entities to manage land and fund transfers established

The evaluation found evidence that the establishment of bodies to manage land and fund transfers has had mixed results. The Inuvialuit and the Naskapi have succeeded in this regard as they have established the management bodies stipulated in their agreements and these bodies continue to function efficiently. The Gwich'in and the Sahtu, while they have established governing bodies to manage land and fund transfers, are seen by outside observers and in several cases members of their own leadership, to have continuing problems due to unclear mandates and lack of capacity. Various explanations were given for the different rates of success.

- The Gwich'in and the Sahtu are said to be negatively affected by many years under the Indian Act, whereas the groups not under the Indian Act were able to maintain their community and cultural integrity more effectively.

- There is a preference among the Sahtu for each community to see itself as unique instead of as a part of a larger, coordinated whole. Sahtu leaders view this as a strength because it means that people residing in communities are more involved in making decisions that affect their lives. They acknowledge that there is a price to be paid in terms of the facility of coordination and the pace of development, but they consider it a price worth paying.

- Inadequate supportive funding is seen by most Aboriginal respondents and a few federal officials, as contributing to an ongoing lack of capacity to manage land and fund transfers. The funding issue is also viewed by the Aboriginal leaders and government observers as affecting the ability of groups, especially the Gwich'in and the Sahtu, to hire professional expertise to help in management and planning.

The Gwich'in and Sahtu leaders take the position that the Gwich'in Tribal Council and the Sahtu Secretariat have found that under the terms of the agreement they have to meet a wide array of increased governance-related responsibilities, for which no targeted funding is available aside from the land claim transfer. Band support funding covers functions that existed prior to the agreements and therefore is not viewed as contributing to the new responsibilities. The result is that they are unable to function as effectively as they should in protecting the interests of their people and in fostering sustainable economic and social development. Under the Indian Act, both groups receive core funding for a variety of functions and for administrative costs. However, they point to the fact that their responsibilities have increased and become much more complex under the land claim agreements, so the net effect is to leave them less able to lead effectively. Naskapi leaders also indicated that, while land and funding transfers have taken place as planned and as structures have been established as intended, overall government financial commitment to support economic and social development has been weak. This is viewed as indicative of a lack of federal commitment to help achieve the long-term goals of the agreements.

4.2 Clarity and Certainty of Ownership and Access to Land and Resources

One of the primary impetuses for the negotiation of the land claims agreements was the desire to establish an environment that was more conducive to resource development and other economic development opportunities, while protecting the interests of the Aboriginal people making claim to the settlement areas. Key to this was a greater degree of clarity and certainty as to the ownership of land and access to land and resources. An environment of greater certainty as to ownership and access was intended to reduce the risk associated with legal challenges and facilitate investment. Results from the evaluation conclude that:

- The land claim agreements have succeeded, with minor exceptions, in establishing clarity and certainty regarding land ownership and access.

- There have been several lawsuits filed in the JBNQA and NEQA settlement regions by non-beneficiaries, but no other legal challenges associated with land ownership and access or resource-related rights.

- Formal dispute resolution bodies have rarely been used to settle land ownership and access issues and there have been few informal disputes.

- Three issues related to land use that arose early on in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region have been settled after lengthy delays.

- Information on land ownership and access is readily available and industry has been informing itself and responding positively to the new circumstances, however, there remains some lack of clarity with regard to ownership and access among residents in the NWT settlement areas.

Clarity and certainty

There is a consensus among the vast majority of those consulted for this evaluation that clarity and certainty regarding ownership and access to land and resources, while not absolute, have been achieved in the agreements. When issues arise, they are more likely to be between Aboriginal groups and the federal government, not industry. Issues typically relate more to variances in interpretation, specific land use and access, or government procurement disputes as opposed to a lack of clarity. Industry is seen to be working to ensure that they understand ownership and regulations governing access in order to maintain good relations with Aboriginal people in the settlement areas.

Legal challenges