First Nations in Canada

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Part 1 – Early First Nations: The six main geographical groups

- Part 2 – History of First Nations - Newcomer Relations

- Part 3 – A Changing Relationship: From allies to wards (1763-1862)

- Part 4 – Legislated Assimilation - Development of the Indian Act (1820-1927)

- Part 5 – New Perspectives - First Nations in Canadian society (1914-1982)

- Part 6 – Towards a New Relationship (1982-2008)

Introduction

First Nations in Canada is an educational resource designed for use by young Canadians; high school educators and students; Aboriginal communities; and anyone interested in First Nations history. Its aim is to help readers understand the significant developments affecting First Nations communities from the pre-Contact era (before the arrival of Europeans) up to the present day.

The first part of this text —"Early First Nations"— presents a brief overview of the distinctive cultures of the six main geographic groups of early First Nations in Canada. This section looks at the principal differences in the six groups' respective social organization, food resources, homes, modes of transportation, clothing, and spiritual beliefs and ceremonies.

Parts two through six of this text trace the relationship between First Nations and newcomers to Canada from the very first encounter up to the government's historic apology in June 2008 to all former students of Indian Residential Schools. In this apology, the Government of Canada expressed deep regret for the suffering individual students and their families experienced because of these schools. The government also acknowledged the harm that residential schools and assimilation policies had done to Aboriginal people's cultures, languages and heritage.

Today the Government of Canada is working in partnership with First Nations in this new era of reconciliation to build stronger First Nations communities. All across the country, this crucial collaborative work is taking place in areas as diverse as First Nations economies, education, governance, social services, human rights, culture and the resolution of outstanding land claims.

Part 1 – Early First Nations: The Six Main Geographical Groups

Before the arrival of Europeans, First Nations in what is now Canada were able to satisfy all of their material and spiritual needs through the resources of the natural world around them. For the purposes of studying traditional First Nations cultures, historians have therefore tended to group First Nations in Canada according to the six main geographic areas of the country as it exists today. Within each of these six areas, First Nations had very similar cultures, largely shaped by a common environment.

The six groups were: Woodland First Nations, who lived in dense boreal forest in the eastern part of the country; Iroquoian First Nations, who inhabited the southernmost area, a fertile land suitable for planting corn, beans and squash; Plains First Nations, who lived on the grasslands of the Prairies; Plateau First Nations, whose geography ranged from semi-desert conditions in the south to high mountains and dense forest in the north; Pacific Coast First Nations, who had access to abundant salmon and shellfish and the gigantic red cedar for building huge houses; and the First Nations of the Mackenzie and Yukon River Basins, whose harsh environment consisted of dark forests, barren lands and the swampy terrain known as muskeg.

The following section highlights some of the wide variations in the six groups' social organization, food resources, and homes, modes of transportation and clothing — as well as spiritual beliefs widely shared by all Early First Nations.

Social Organization

Most Woodland First Nations were made up of many independent groups, each with its own hunting territory. These groups usually had fewer than 400 people. A leader generally won his position because he possessed great courage or skill in hunting. Woodland First Nations hunters and trappers had an intimate knowledge of the habitats and seasonal migrations of animals that they depended on for survival.

Unlike Woodland First Nations, Iroquoian First Nations did not migrate in search of food. Excellent farmers, these southern peoples harvested annual food crops of corn, beans and squash that more than met their needs. An abundance of food supplies made it possible for the Iroquoian First Nations (now known as the Haudenosaunee, or People of the Longhouse) to found permanent communities and gave them the leisure time to develop complex systems of government based on democratic principles.

The Huron-Wendat, for example, had a three-tier political system, consisting of village councils, tribal councils and the confederacy council. All councils made decisions on a consensus basis, with discussions often going late into the night until everyone reached agreement.

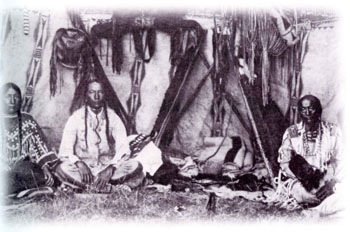

On the Plains, the individual migratory groups, each with their own chief, assembled during the summer months for spiritual ceremonies, dances, feasts and communal hunts. Even though each group was fiercely independent, Plains First Nations had military societies that carried out functions such as policing, regulating life in camp and on the march, and organizing defences.

The social organization of several Plains First Nations was influenced by their neighbours and trading partners—the First Nations of the Pacific Coast. As a result, the Dakelh-ne (Carrier), Tahltan and Ts'ilh'got'in (Chilcotin) adopted the stratified social systems of the Pacific Coast Nations, which included nobles, commoners and slaves.

In addition to these three distinct social orders, Pacific Coast First Nations had a well-defined aristocratic class that was regarded as superior by birth. The basic social unit for all First Nations in this part of the country was the extended family (lineage) whose members claimed descent from a common ancestor. Most lineages had their own crests, featuring representations of animal or supernatural beings that were believed to be their founders. The most famous method of crest display was the totem pole consisting of all the ancestral symbols that belonged to a lineage.

The people of the Mackenzie and Yukon River Basins lived in a vast homeland where game animals were very scarce and the winters were long and severe. As was true of most First Nations across the country, those of the Mackenzie and Yukon River Basins were primarily occupied with day-to-day survival. As such, First Nations were divided into several independent groups made up of different family units who worked together. Each group hunted a separate territory, with individual boundaries defined by tradition and use. A group leader was selected according to the group's needs at a particular time. On a caribou hunt, for example, the most proficient hunter would be chosen leader.

Food Resources

All First Nations across the country hunted and gathered plants for both food and medicinal purposes. The actual percentage of meat, fish and plants in any First Nation's diet depended on what was available in the local environment.

The Woodland First Nations (and all First Nations in the northern regions) hunted game animals with spears and bows and arrows. These First Nations also used traps and snares—a type of noose that caught the animal by the neck or leg. Northern hunters, such as the Gwich'in, built elaborate routing fences with stakes and brush. The Gwich'in used these fences to stampede animals into the area where snares had been set to trap them. To provide for times of hardship, the people dried large stores of meat, fish and berries during the summer. During the winter, to keep frozen meat safe from animals such as the wolverine, some First Nations of the Mackenzie and Yukon River Basins stored their food high in a tree with its trunk peeled of bark.

Even though the Haudenosaunee had plenty of meat, fish and fowl available to them in the wild, they lived mainly on their own crops—corn, beans and squash, which were called "The Three Sisters." The men cleared the land for planting, chopping down trees and cutting the brush, while the women planted, tended and harvested the crops. After about 10 years, when the land became exhausted, the people would relocate and clear new fertile fields.

Because the buffalo was the main object of their hunt, Plains First Nations had a hunting culture that was highly developed over thousands of years. Communal hunts took place in June, July and August when the buffalo were fat, their meat prime and their hides easily dressed.

A single buffalo provided a lot of meat, with bulls averaging about 700 kilograms. Eaten fresh, the meat was roasted on a spit or boiled in a skin bag with hot stones, a process that produced a rich, nutritious soup. Just as common was the dried buffalo meat known as jerky, which could be stored for a long time in rawhide bags. Women also prepared high-protein pemmican—dried meat pounded into a powder, which was then mixed with hot, melted buffalo fat and berries. A hunter could easily carry this valuable food stuff in a small leather bag. Pemmican later became a staple in the diet of fur traders and voyageurs.

Salmon was the primary food source for the First Nations of the Plateau. Even the Tahltan hunters of the north assembled each spring at the fishing places to await the arrival of the first salmon. People used dip nets and built weirs in the shallows of swift waters to trap schools of fish. Of the thousands of salmon caught each year, a very small proportion was eaten fresh. The remainder was cleaned, smoked and stored for winter in underground pits lined with birch bark. Wild vegetable foods—chiefly roots and berries—also formed an important part of the diet of the Plateau First Nations, particularly the Interior Salish.

The vast food resources of the ocean—salmon, shellfish, octopus, herring, crabs, whale and seaweed—made it possible for Pacific Coast First Nations to settle in permanent locations. Unlike the Haudenosaunee who relocated every 10 years or so, Pacific Coast First Nations usually built permanent villages. Some village sites show evidence of occupation for more than 4,000 years. Like Plateau First Nations, those of the Pacific Coast dried most of their salmon in smokehouses so that it could be stored and eaten later. Fish oil also played an important part in people's diet, serving as a condiment with dried fish during the winter months. A highly valued source of oil was eulachon, a type of smelt.

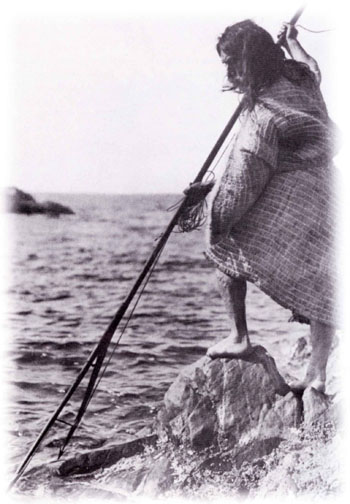

The Coast Tsimshian, Haida and Nuu-chah-nulth all hunted sea lion and sea otter, going out into the ocean with harpoons in slim dugout canoes. However, the most spectacular of all marine hunts was the Nuu-chah-nulth's pursuit of the whale. Nuu-chah-nulth whaling canoes were large enough for a crew of eight and the harpooner, who was armed with a harpoon of yew wood about four metres long and sat directly behind the prow.

Homes

Because of their migratory way of life, First Nations of the Woodland, Plains and Mackenzie and Yukon River Basins all built homes that were either portable or easily erected from materials found in their immediate environments. Woodland and northern peoples' homes were essentially a framework of poles covered with bark, woven rush mats or caribou skin, called tipis.

Plains First Nations' tipi poles were usually made from long slender pine trees. These were highly valued because replacements were not easy to find on the Prairies. The average tipi cover consisted of 12 buffalo hides stitched together. To prevent drafts and to provide interior ventilation, an inner wall of skins about two metres high was often fastened to the poles on the inside. Women made, erected and owned the tipis.

Unlike nomadic First Nations, the Haudenosaunee had relatively permanent villages. The longhouse was the most striking feature in an Haudenosaunee village. This structure consisted of an inverted U shape made of poles, which were then covered with slabs of bark. Longhouses were usually about 10 metres wide, 10 metres high and 25 metres long. Each longhouse was headed by a powerful matriarch who oversaw her extended family's day-to-day affairs.

Among First Nations of the Plateau, the subterranean homes of the Interior Salish were unlike those of other First Nations in the country. The Interior Salish dug a pit, usually about two metres deep and from six to twelve metres wide, in well-drained soil, typically near a river. This location meant that clean water, fish and a means of transport were all readily accessible. The Interior Salish then covered the pit with a framework of poles and insulated this dwelling with spruce boughs and earth that was removed from the pit. An opening approximately 1.25 metres square was left at the top and served as both the doorway and smoke-hole. People entered the house with the help of steps carved into a sturdy, slanting log, the top of which protruded out of the opening of the pit house.

Massive forests of red cedar along the Pacific Coast allowed the First Nations who lived in this part of the country to build huge homes. Excellent carpenters, these First Nations used chisels made of stone or shell and stone hammers to split the soft, straight-grained cedar into wide planks. One of the largest traditional homes ever recorded from the pre-contact era was in a Coast Salish village. It was 170 metres long and 20 metres wide. Because Pacific Coast houses were so large, they could accommodate several families, each with its own separate living area and hearth.

Modes of Transportation

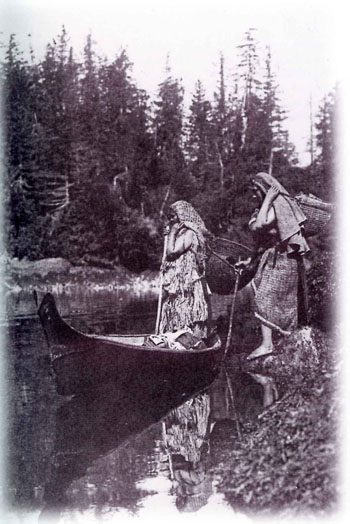

Woodland First Nations constructed birch bark canoes that were light, durable and streamlined for navigating the numerous rivers and lakes in this area. Canoe builders stitched bark sheets together and then fastened them to a wooden frame using watup—white spruce root that had been split, peeled and soaked. The vessel's seams were waterproofed with a coating of heated spruce gum and grease.

In the Mackenzie and Yukon River Basins, birch trees did not grow as large as in the southern regions of the country. However, many northern First Nations were able to construct long canoes, using spruce gum to seal the seams between the smaller pieces of bark.

Some Haudenosaunee also built bark-covered canoes. However, these First Nations mainly travelled by land. Exceptional runners, the Haudenosaunee could cover extremely long distances in a very short time.

When the horse was introduced on the Plains by European explorers around 1700, the peoples of the Plains First Nations readily adapted and became skilled riders. Within 100 years of its introduction, the horse was an essential part of Plains First Nations culture—in hunting, warfare, travel and the transportation of goods. Before that, the principal means of transporting goods and household possessions was the dog and travois—two long poles hitched to a dog's sides, to which a webbed frame for holding baggage was fastened.

Pacific Coast First Nations travelled almost exclusively by water, using dugout canoes made of red cedar. Size varied according to a canoe's function. A small hunting canoe for one or two men would be about five metres long. The Haida built very large canoes. Some Haida canoes were more than 16 metres long and two metres wide, and could carry 40 men and two metric tons of cargo.

The actual construction process of a canoe could last three to four weeks and had its own rituals, including prayer and sexual abstinence for the canoe maker. These talented men stretched a canoe hull using a steam-softening process. Water was poured into the hollow and brought to a boil with hot stones. Wooden stretchers were then inserted to hold the sides of the canoe apart while it cooled.

For winter travel, all First Nations built some form of snowshoe with a wood frame and rawhide webbing. The shape and size of snowshoes varied due to what sort of terrain was being travelled.

Clothing

All First Nations across the country, with the exception of the Pacific Coast, made their clothing—usually tunics, leggings and moccasins—of tanned animal skin. Woodland and northern First Nations used moose, deer or caribou skin. Plains First Nations mostly used light animal skins, such as buffalo, antelope, elk or deer.

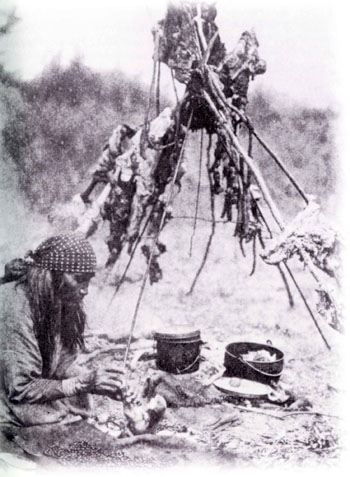

Women prepared the animal skins and used a smoke tanning process to preserve the hides. Bone needles were used to sew the garments with sinew from the back or legs of a caribou, moose or deer. In winter, people wore robes of fur for extra warmth. Caribou skins were particularly valued by First Nations of the Mackenzie and Yukon River Basins because caribou hair is an excellent insulator.

Whenever weather permitted, men from Pacific Coast First Nations went unclothed. Coast Tsimshian women wore skirts of buckskin, but elsewhere on the Pacific Coast the women's skirts were woven of cedar bark that had been shredded to produce a soft fibre. Neither men nor women of Pacific Coast First Nations had footwear of any kind. In rainy weather these coastal people wore woven bark rain capes and wide-brimmed hats of woven spruce roots. The Nuu-chah-nulth and Kwakwaka'wakw also made a distinctive long robe woven from yellow cedar bark. Some of these robes were interwoven with mountain goat wool and the most luxurious had borders of sea otter fur.

Any decorative touches on clothing came from nature. Many Woodland, Haudenosaunee and northern First Nations used dyed porcupine quills to embroider designs on their clothing and moccasins. Men and women coloured their clothing with red, yellow, blue and green dyes derived from flowers, fruits, roots and berries. The men of the Plains First Nations also regularly wore face paint, and a red dye derived from the clay was a very popular colour.

Spiritual Beliefs

All First Nations believed that their values and traditions were gifts from the Creator. One of the most important and most common teachings was that people should live in harmony with the natural world and all it contained.

In oral stories and legends that Elders passed from one generation to another, First Nations children learned how the world came into being and that they were a part of the whole of creation. People gave thanks to everything in nature, upon which they depended for survival and development as individuals and as members of their communities. First Nations treated all objects in their environment—whether animate or inanimate—with the utmost respect.

This deep respect that First Nations cultivated for every thing and every process in the natural world was reflected in songs, dances, festivals and ceremonies. Among the Woodland First Nations, for example, a hunter would talk or sing to a bear before it died, thanking the animal for providing the hunter and his family with much-needed food.

In keeping with their farming culture, the Haudenosaunee held six to eight festivals a year relating to the cultivation of the soil and ripening of fruits and berries. There was a seven-day festival to give thanks when corn was planted, for example, and another when it was green. A third festival was held when corn was harvested.

First Nations of the Pacific Coast had many rituals to give thanks and celebrate the annual salmon run. These rituals included a welcoming ceremony and offerings to the first salmon of the year.

For the principles that guided their day-to-day conduct, many First Nations shared value systems similar to the Seven Grandfather Teachings of the Anishnaabe peoples. These teachings stressed Wisdom, Love, Respect, Bravery, Honesty, Humility and Truth as the values that enable people to live in a way that promotes harmony and balance with everyone and everything in creation.

Part 2 – History of First Nations – Newcomer Relations

First Encounters – Military and Commercial Alliances

(First Contact to 1763)

Indigenous peoples occupied North America for thousands of years before European explorers first arrived on the eastern shores of the continent in the 11th century. These newcomers were Norse explorers and settlers, moving ever-westward from Scandinavia to Iceland and Greenland, and eventually to the island of Newfoundland. There they founded North America's first European colony at L'Anse aux Meadows. Although this colony was short-lived, it marked the beginning of European exploration and migration that would radically change the lives of North America's Indigenous peoples.

European Colonial Settlements and the Fur Trade

In the 1500s Europeans returned to the eastern shores of North America to establish settlements. By that time, many Europeans had heard from returning fishermen about the wealth of resources that the New World offered. Attracted by the Grand Banks' teeming cod stocks, Basque, Breton, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Irish and English fishermen had already made contact and traded with the Mik'maq, Maliseet and Passamaquoddy peoples of the Eastern seaboard. As they returned each summer to fish and dry-cure their catch, these fishermen developed an informal trade system with First Nations, exchanging European goods for furs.

There was soon a network of competing colonies throughout the Americas as the various European powers pushed to expand their own wealth and influence in this New World. In North America, the British and the French quickly became the dominant powers. By the early 1600s the British had established several colonies and begun settlement on a large scale. The bases of France's North American empire were the colonies of Acadia in the Maritimes and New France in the St. Lawrence Valley.

Soon after founding these colonies, the two powers cemented alliances with First Nations to support their commercial interests, which included the fur trade. The British allied with the Iroquois Confederacy (now known as the Haudenosaunee, or People of the Longhouse, this group consisted of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca First Nations) and the First Nations of the Allegheny Mountain range. The French allied with First Nations north of the St. Lawrence River (the Huron, Algonquin, Odawa and Montagnais) and in Acadia (the Mi'kmaq, Maliseet and Passamaquoddy). Using the long-established indigenous trade routes of the Interior, the English and French and their First Nations allies developed a vast trade focused on beaver pelts, that spread across North America. This trade spurred new European explorations throughout the Great Lakes basin, into the Prairies and down the Mississippi River.

Military Alliances and Conflict

French and British explorers, fur traders and soldiers followed the trade routes inland. There they established a network of forts and posts to supply their First Nations trading partners and confirm their presence. First Nations quickly adapted to this new commerce, which brought them European goods such as iron wares and firearms. The fur trade was so profitable and important that the various European and First Nations interests often clashed violently throughout the 16th and 17th centuries. Competition between groups such as the Haudenosaunee mentioned above and the Huron resulted in all-out warfare. In the mid-1600s, the Huron were driven from their traditional territories around Georgian Bay.

In 1701, this tumultuous era came to an end when France and 40 First Nations signed a treaty in Montreal known as the Great Peace. Through the agreement, the various First Nations in the Great Lakes basin promised to stop violent attacks and to share the lands, as "a dish with two spoons." Moreover, just prior to the Montreal conference, Haudenosaunee leaders had agreed to sell all of the lands of the Great Lakes to the British in exchange for their protection and the continued right to hunt and fish throughout the territory. The Haudenosaunee not only attained a stable peace with the French and its allies, but also secured British protection for their lands and interests.

As French and British colonies pushed further inland, their competition for control of the rich Interior of North America became a new theatre of war in the power struggles erupting across Europe. These power struggles, particularly between the British and the French, transformed their respective commercial partnerships with First Nations into vital military alliances that brought much needed support to both camps. Desperate for military assistance ahead of what would turn out to be the final French–British conflict in North America (the Seven Years' War of 1756–1763), British administrators created the Indian Department in 1755 to coordinate alliances with the powerful Haudenosaunee. The new Department also tried to resolve concerns regarding colonial fraud and abuses against First Nations and their lands along the colonial frontier.

In 1760, the fall of Montreal—the last French stronghold on the St. Lawrence—put an end to French colonial efforts in what would become Canada. The British victory led to a realignment of the First Nations alliances that had been in place for more than 150 years. Across the former colonies of New France and Acadia, the British undertook a series of treaties to secure the neutrality of First Nations and to establish peaceful relations. In the Maritime region, where lands had been hotly contested since the early 1700s, the British and the Mi'kmaq, Maliseet and Passamaquoddy peoples entered into dozens of these "Peace and Friendship" treaties. In 1760, the Aboriginal allies of New France called upon the British to recognize their neutrality in the Seven Years War and concluded the Treaty of Swegatchie and the Murray Treaty.

Although Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of the Indian Department, worked hard at smoothing relations with the sceptical former allies of the French, he was not entirely successful. Shortly after the fall of Montreal, the Odawa leader Pontiac, doubting British intentions and motives, led a series of attacks against British military positions throughout the Great Lakes region. Nevertheless, a combination of military and diplomatic missions enabled Johnson and the Indian Department to establish peaceful, if somewhat uneasy relations with the various First Nations of the Interior.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Treaty of Paris in 1763 ended more than 150 years of European competition and conflict. Through this agreement, France ceded its colonial territories in what is now Canada, including Acadia, New France and the Interior lands of the Great Lakes and the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. Britain was now the primary European power throughout much of North America, controlling all of the valuable commercial fur trade. Despite this dominance, the British did not fully control the continent. British administrators realized that the success of Britain's North American colonies depended upon stable and peaceful relations with First Nations. To help achieve this, King George III issued a Royal Proclamation in 1763, which specified how the colonies were to be administered. This wide-ranging document established a firm western boundary for the colonies. All the lands to the west of this boundary became "Indian Territories" where there could be no settlement or trade without the permission of the Indian Department.

The Proclamation established very strict protocols for all dealings with First Nations. From 1763 onward, the Indian Department became the primary point of contact between First Nations and the colonies. In addition, only the Crown could purchase land from a First Nation, which was done by officially sanctioned Crown representatives negotiating with an interested First Nation in a public meeting. All other land purchases were to be considered invalid and were dismissed.

The original intent of the Royal Proclamation was to slow the uncontrolled western expansion of the colonies and tightly control the relationship between First Nations and colonists. But crucially, the Proclamation also became the first public recognition of First Nations rights to lands and title.

Part 3 - A Changing Relationship – From Allies to Wards

(1763–1862)

Until the late 18th century, the relationship between First Nations and the British Crown was still very much based on commercial and military interests. The Indian Department had one primary goal for the British administration throughout the Great Lakes basin—to maintain the peace between the small number of British soldiers and traders stationed at far-flung trading posts and the far more numerous and well-armed First Nations. Under Sir William Johnson's direction, the Indian Department acted as an intermediary between the military and First Nations leaders, securing lands for forts; assuring access to trade, furs and goods; issuing yearly presents; and organizing peace conferences. As Johnson made clear in a letter to the British government, the powerful position of First Nations meant that British commercial interests could only flourish in the Interior if the Crown took definite steps to protect those interests.

Treaties and a Growing Colony

The outbreak of the American War of Independence and Britain's subsequent recognition of the United States of America in 1783 had a dramatic impact on the relationship between the British Crown and its First Nations allies. The loss of the American colonies brought some 30,000 United Empire Loyalist refugees to the remaining British colonies in North America. A powerful group of people who had lost everything because of their support for the British cause, these Loyalists asked colonial administrators for new lands.

Settlers were not the only refugees from the newly independent United States. First Nations who fought alongside the British were also dispossessed by the war, especially the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy (this group consisted of the Five Nations Confederacy mentioned above, plus the Tuscarora First Nation). Their lands were unilaterally ceded to the Americans by the 1783 Treaty of Versailles. "His Majesty's Loyal Allies" from the Iroquois Confederacy were now refugees in Montreal and were asking for compensation for their efforts on the Crown's behalf. In response, officials from the Indian Department negotiated a series of land surrender treaties with the various Anishinaabeg peoples (Odawa, Ojibwa and Algonquin First Nations) inhabiting the lands along the St. Lawrence River and around the Great Lakes. These land surrenders, which largely preceded the arrival of settlers to the area, allowed for the remarkably peaceful establishment of an agricultural colony. To help compensate their First Nations allies for the losses incurred during the war with the Americans, the British Crown set aside two parcels of lands as reserves for the Six Nations—one at the Bay of Quinte and the other along the Grand River.

In the last decades of the 18th century, British military leaders and the Indian Department still placed great value on their strong military alliances with First Nations. They feared future conflict with the new American state to the south and saw the numerous First Nations warriors as essential to their colony's defence. The Indian Department worked to bolster the damaged alliances by trying to secure fair deals on land surrenders and by protecting First Nations lands. The Department also issued yearly presents and weaponry during gatherings and conferences with First Nations chiefs and leaders, even those in American territories. These alliances were tested and proved to be strong as war did eventually break out between Britain and its former American colonies. During the War of 1812, First Nations fought alongside the British and Canadian colonists against the American invasion of what is now southern Ontario.

Shifting Relationships

Once peace returned to North America, new immigrants and colonists continued to arrive. Less than 50 years after the first land surrenders for settlers in Upper Canada, the non-First Nations population outnumbered the settler population in the Great Lakes basin. To provide land for new settlers' farms, the pace of land surrenders increased. Some 35 sales were concluded, covering all the lands of Upper Canada—from the productive agricultural lands in the south to the natural resource-rich lands of Lake Superior and Georgian Bay.

As settlers demanded more and more property, they began to pressure the colonial administration for the lands held by First Nations. Instead of a bastion of colonial defence, the colony's First Nations populations were now regarded as an impediment to growth and prosperity. Not only had military threats to the colonies faded with the end of the War of 1812, but the colonial militia was able to draw on the ever-growing settler population to meet the colony's defensive needs. In the decades following the War of 1812, British administrators therefore began to regard First Nations as dependents, rather than allies.

By the 1830s, with more and more lands surrendered for settlement, only pockets of First Nations lands remained in Upper Canada. For the most part, the land surrender treaties did not create sizeable reserves for the First Nations signatories. First Nations thus increasingly lost access to hunting grounds and became a dispossessed people on their former lands. A treaty concluded in 1836 by the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, Sir Francis Bond Head, established Manitoulin Island in Georgian Bay as a reserve for the dispossessed First Nations population. The goal was to encourage these landless peoples to relocate to the island where they would be removed from the more harmful aspects of colonial society (specifically alcohol and prostitution) and where they would adapt to the new colonial reality at a controlled pace. However, few First Nations actually relocated to Manitoulin Island. Most continued to live on small plots of lands set aside by the treaties or on the lands of religious missions trying to convert them to Christianity. Some squatted on Crown Lands, living an increasingly destitute life. Meanwhile, the Crown continued to conclude land surrender treaties with First Nations until 1862.

As settlement lands were filled, attention turned for the first time to northern areas where minerals had been discovered along the shores of Lake Superior and Lake Huron. As a result, the Robinson-Huron and Robinson-Superior treaties of the 1850s were negotiated with the various Anishinaabeg peoples inhabiting the area. These two treaties, unlike any previously negotiated treaties, would become the template for future agreements with First Nations in the West. Specifically, the two Robinson treaties ceded First Nations lands and rights to the Crown in exchange for reserves, annuities and First Nations' continued right to hunt and fish on unoccupied Crown lands. This formula to conclude agreements with numerous bands for large tracts of lands would become the model for the Post-Confederation Numbered Treaties.

The Hudson's Bay Company

While Britain established its new colony on the St. Lawrence, the Company of Adventurers, better known as the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), continued to trade as it had done since 1670. With an exclusive monopoly and a charter for all the lands of the Hudson Bay watershed, the HBC traded with the First Nations of what is now Northern Quebec, Ontario and Manitoba. In search of rich supplies of furs for the European market, this trade extended along the coasts of the Hudson and James bays. Only peripherally affected by the nearly continuous colonial conflict between France and Britain, the HBC was able to establish a series of posts at strategic major rivers. These early posts, such as Fort Albany and York Factory, became the base for an extensive trade alliance with the Cree. In exchange for a wide variety of goods (knives, kettles, beads, needles and blankets), the Cree traded vast amounts of animal furs from the Interior. As the fur trade grew more lucrative, the Cree became a sort of intermediary between the Company and the Interior groups. They collected furs and pelts from other First Nations hunters and took them to the HBC posts on the coast. Because of the HBC's monopoly over all trade on lands where the waters flowed into Hudson Bay, this trade relationship proved very profitable for both parties.

Not all parties, however, were happy with the Company's monopoly over some of the richest fur territories in North America. Following the transfer of New France to the British, French traders based in Montreal began to look for new sources of fur. Several new companies began to challenge the HBC, the most successful being the Northwest Company. Using the system of Interior trading posts and routes established by the French before 1763, the Nor'Westers, as they were known, exploited the lands of the Upper Great Lakes by going out to trade and collect the furs themselves. The Northwest Company, aided by the paddling and hauling skills of French-Canadian, Métis and First Nations voyageurs, went directly to the source of the furs. In this way, they were able to redirect a large quantity of furs away from the Cree intermediaries and the HBC posts far to the north. Using the Ottawa River route from Montreal up to Lake Nippissing and across to Lake Superior, the Northwest Company controlled the bulk of the fur trade heading to Montreal and across to Europe. From their company's primary post, Fort William (near present-day Thunder Bay), the Nor'Westers extended their reach into the vast Prairies of North America.

By going into the Interior and trading directly with First Nations hunters, the Northwest Company disrupted the long-standing relationship between the HBC and its Cree intermediaries. Faced with a sharp decline in fur stocks, the HBC governors in London responded by adopting their rival's tactics and abandoning the use of First Nations middlemen. During the first two decades of the 19th century, the HBC and Northwest Company pushed further down the North and South Saskatchewan, the Assiniboine and the Athabasca rivers (among others) in a race to get to First Nations hunters and their fur stocks. This competition not only pitted the traders against each other, but First Nations also joined the fray in an attempt to secure the best prices and goods for their furs. In 1821, after a bloody decade of violence and conflict on the Prairies, the two companies merged into a new and reinvigorated Hudson's Bay Company. The renewed HBC now stretched across the northern half of the continent and held a near total monopoly on trade from the Pacific Coast to Hudson Bay and down to Montreal.

This long history of trade, commerce and competition brought about major changes for the First Nations populations of the northern Plains. Above all, the European desire for fur radically transformed Indigenous economies. Rather than small-scale hunting for furs, First Nations were dedicating more and more time and resources to the seemingly endless European demand for animal pelts. The HBC's desire for bison pelts and pemmican (a type of preserved bison meat popular among traders and voyageurs) transformed the Plains First Nations' buffalo hunt from one of subsistence to extensive commercial exploitation. Trade patterns shifted towards the northern HBC posts and later to the Interior trading posts that were scattered across the Prairies. Traders who had to ship goods down the rivers to central depots such as Fort William hired First Nations men as labourers and porters. All of these activities contributed to a wide-scale diffusion of European goods, especially iron wares, knives and firearms, and to First Nations' dependence on these goods.

A second major impact of the extended fur trade was increased contact between First Nations, traders and settlers, which would have a dramatic effect on First Nations over the long term. The far-flung and isolated trading posts became gathering places for many groups—not only for trade with the HBC, but also for traders and First Nations themselves. This proximity to traders meant easy access to alcohol, which would have devastating effects on First Nations.

In 1812, the Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, the Earl of Selkirk, established a colonial settlement where the Red and Assiniboine rivers meet. Plagued by poor planning and the ongoing conflict between the HBC and the Northwest Company, this initial attempt to organize a colony in the Interior ended in failure. However, a few settlers and Company men did remain in the area and lived in the Interior year-round. Eventually, these people helped form a more established community along the Red River. Decades of intermarriage between HBC traders and voyageurs with First Nation women created a new and distinct Aboriginal group—the Métis—centred at the junction of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. This close-knit community merged and adopted European and First Nations customs and lifestyles to meet the needs of the growing frontier settlement.

Part 4 - Legislated Assimilation – Development of the Indian Act

(1820–1927)

"Civilizing the Indian"

As First Nations' military role in the colony waned, British administrators began to look at new approaches to their relationship. In fact, a new perspective was emerging throughout the British Empire about the role the British should play with respect to Indigenous peoples. This new perspective was based on the belief that British society and culture were superior; there was also a missionary fervour to bring British "civilization" to the Empire's Indigenous people. In the colonies of Upper and Lower Canada, the Indian Department became the vehicle for this new plan of "civilization." The British believed it was their duty to bring Christianity and agriculture to First Nations. Indian agents accordingly began encouraging First Nations to abandon their traditional lifestyles and to adopt more agricultural and sedentary ways of life. As we now know, these policies were intended to assimilate First Nations into the larger British and Christian agrarian society.

Starting in the 1820s, colonial administrators undertook many initiatives aimed at "civilizing" First Nations. One early assimilation experiment took place at Coldwater-Narrows, near Lake Simcoe in Upper Canada. A group of Anishinaabe were encouraged to settle in a typical colonial-style village where they would be instructed in agriculture and encouraged to adopt Christianity and abandon hunting and fishing as a means of subsistence. But because of poor management by the Indian Department, chronic underfunding, a general lack of understanding of First Nations cultures and values, and competition between various religious denominations, the Coldwater-Narrows experiment was short-lived and a dismal failure.

Indian Legislation

Despite initial problems, the "civilization" program was to remain one of the central tenets of Indian policy and legislation for the next 150 years. One of the first such pieces of legislation was the Crown Lands Protection Act, passed in 1839. This Act made the government the guardian of all Crown lands, including Indian Reserve lands. The Act responded to the fact that settlement was occurring faster throughout the 1830s than the colony could manage. Squatters were already settling on unoccupied territory, both Crown lands and Indian reserves. The statute was thus the first to classify Indian lands as Crown lands to be protected by the Crown. The Act also served to secure First Nations interests by limiting settlers' access to reserves. More legislation protecting First Nations interests were passed in 1850, limiting trespassing and encroachment on First Nations reserve lands. This legislation also provided a definition of an "Indian", exempted First Nations from taxation and protected them from creditors. In 1857, the British administration introduced the Gradual Civilization Act. This legislation offered 50 acres of land and monetary inducements to literate and debt-free First Nations individuals provided they abandoned their traditional lifestyle and adopted a "civilized" life as a "citizen".

In 1860, the Management of Indian Lands and Property Act (Indian Land Act) brought about another fundamental change in First Nations' relations with the Crown. This Act transferred authority for Indian affairs to the colonies, enabling the British Crown to dispense with the last of its responsibilities towards its former allies. However, colonial responsibility for the management of "Indians and Indian lands" very soon became a federal responsibility with the creation of the new Dominion of Canada under the 1867 British North America Act. The new nation continued the centralized approach to Indian affairs used by the British. In addition, in 1869 Canada extended its influence over First Nations by the purchase of Rupert's Land (the Hudson's Bay Company lands). The new Dominion was now responsible for addressing the needs and claims of First Nations from the Atlantic to the Rocky Mountains.

Indian Policy in British Columbia

On the West Coast, the relationship between European settlers and the region's First Nation inhabitants developed quite differently from that between settlers and First Nations in the Great Lakes basin. For nearly 50 years, the commercial aspirations of the Hudson's Bay Company had overshadowed settlement in the West. With a trade monopoly for the entire British half of the Oregon territory, the HBC was content to keep its diplomatic dealings with the West Coast First Nations restricted to commercial matters relating to the fur trade.

In 1849, the HBC received a new mandate to establish a colony on Vancouver Island. James Douglas, the HBC's Chief Factor and later colonial Governor after 1854, signed 14 treaties with various Coast Salish communities on Vancouver Island between 1850 and 1854. Under these treaties, the First Nations surrendered land required for settlement around various HBC posts in exchange for lump sum cash payments and goods, and the continued right to hunt and fish. The creation of the colony of British Columbia in 1859 and the rise of local control over colonial administration had a deep and lasting impact on First Nations in the region. Led by colonial surveyor and later lieutenant governor, Joseph Trutch, the colonial assembly slowly retracted the policies established by Douglas during the 1850s. Treaty making did not continue after 1854 because of British Colombia's reluctance to recognize First Nations land rights, unlike all other British colonial jurisdictions. This denial of Aboriginal land title persisted even after British Colombia joined Confederation and ran contrary to the Dominion's recognition of this title in other parts of the country.

The Numbered Treaties

Between 1871 and 1921, Canada undertook a series of land surrender treaties throughout its new territories. The objectives of these surrenders were to fulfil the requirements under the transfer; to secure Canadian sovereignty; to open the land for settlement and exploitation; and to reduce possible conflict between First Nations and settlers. Adhering to the form of the 1850 Robinson Treaties, the Crown negotiated 11 new agreements covering Northern Ontario, the Prairies and the Mackenzie River up to the Arctic. As in the Robinson Treaties, these Numbered Treaties set aside reserve lands for First Nations and granted them annuities and the continued right to hunt and fish on unoccupied Crown lands in exchange for Aboriginal title. Also included in these new treaties were schools and teachers to educate First Nations children on reserves; farming, hunting and fishing equipment; and ceremonial and symbolic elements, such as medals, flags and clothing for chiefs. First Nations were not opposed to this process and in many cases pressured Canada to undertake treaties in areas when it was not prepared to do so. First Nations signatories had their own reasons to enter into treaties with the Crown. On the whole, First Nations leaders were looking to the Crown for assistance in a time of great change and upheaval in their communities. Facing disease epidemics and famine, First Nations leaders wanted the government to help care for their people. They also wanted assistance in adapting to a rapidly changing economy as buffalo herds neared extinction and the HBC shifted its operations to the North.

Throughout the negotiations and in the text of the Numbered Treaties, First Nations were encouraged to settle on reserve lands in sedentary communities, take up agriculture and receive an education. The Treaty Commissioners explained that the reserves were to help First Nations adapt to a life without the buffalo hunt and that the government would help them make the transition to agriculture. These 11 treaties included land surrenders on a massive scale. The Numbered Treaties can be divided into two groups: those for settlement in the South and those for access to natural resources in the North. Treaties 1 to 7 concluded between 1871 and 1877, led the way to opening up the Northwest Territories to agricultural settlement and to the construction of a railway linking British Columbia to Ontario. These treaties also solidified Canada's claim on the lands north of the shared border with the United States. After a 22-year gap, treaty making resumed between 1899 and 1921 to secure and facilitate access to the vast and rich natural resources of Northern Canada.

The Indian Act

In 1876, the government introduced another piece of legislation that would have deep and long-lasting impacts on First Nations across Canada. The Indian Act of 1876 was a consolidation of previous regulations pertaining to First Nations. The Act gave greater authority to the federal Department of Indian Affairs. The Department could now intervene in a wide variety of internal band issues and make sweeping policy decisions, such as determining who was an Indian. Under the Act, the Department would also manage Indian lands, resources and moneys; control access to intoxicants; and promote "civilization." The Indian Act was based on the premise that it was the Crown's responsibility to care for and protect the interests of First Nations. It would carry out this responsibility by acting as a "guardian" until such time as First Nations could fully integrate into Canadian society.

The Indian Act is one of the most frequently amended pieces of legislation in Canadian history. It was amended nearly every year between 1876 and 1927. The changes made were largely concerned with the "assimilation" and "civilization" of First Nations. The legislation became increasingly restrictive, imposing ever-greater controls on the lives of First Nations. In the 1880s, the government imposed a new system of band councils and governance, with the final authority resting with the Indian agent. The Act continued to push for the whole-scale abandonment of traditional ways of life, introducing outright bans on spiritual and religious ceremonies such as the potlatch and sun dance.

The concept of enfranchisement (the legal act of giving an individual the rights of citizenship, particularly the right to vote) also remained a key element of government policy for decades to come. As very few First Nations members opted to become enfranchised, the government amended the Act to enable automatic enfranchisement. An 1880 amendment, for example, declared that any First Nations member obtaining a university degree would be automatically enfranchised. An 1933 amendment empowered the government to order the enfranchisement of First Nations members meeting the qualifications set out in the Act, even without such a request from the individuals concerned. In 1927, the government added yet another new restriction to the Act. In response to the Nisga'a pursuit of a land claim in British Columbia, the federal government passed an amendment forbidding fundraising by First Nations for the purpose of pursuing a land claim without the expressed permission of the Department of Indian Affairs. This amendment effectively prevented First Nations from pursuing land claims of any kind.

Indian Education and Residential Schools

In 1883, Indian Affairs policy on First Nations education focused on residential schools as a primary vehicle for "civilization" and "assimilation". Through these schools, First Nations children were to be educated in the same manner and on the same subjects as Canadian children (reading, writing, arithmetic and English or French). At the same time, the schools would force children to abandon their traditional languages, dress, religion and lifestyle. To accomplish these goals, a vast network of 132 residential schools was established across Canada by the Catholic, United, Anglican and Presbyterian churches in partnership with the federal government. More than 150,000 Aboriginal children attended residential schools between 1857 and 1996.

Part 5 - New Perspectives – First Nations in Canadian Society

(1914–1982)

Despite decades of difficult and painful living conditions for First Nations under the restrictive regulations of the Indian Act, many First Nations answered the call to arms during both World Wars and the Korean War. Approximately 6,000 Aboriginal soldiers from across Canada served in the First World War alone. By the late 1940s, social and political changes were underway that would mark the start of a new era for First Nations in Canada. Several First Nations leaders emerged, many of them drawing attention to the fact that thousands of their people had fought for their country in both World Wars. First Nations across the country began to create provincially based organizations that forcefully expressed their peoples' desire for equality with other Canadians, while maintaining their cultural heritage.

Rolling Back Paternalism

In 1946, a special joint parliamentary committee of the Senate and the House of Commons undertook a broad review of Canada's policies and management of Indian affairs. For three years, the committee received briefs and representations from First Nations, missionaries, school teachers and federal government administrators. These hearings brought to light the actual impact of Canada's assimilation policies on the lives and well-being of First Nations. The committee hearings were one of the first occasions at which First Nations leaders and Elders were able to address parliamentarians directly instead of through the Department of Indian Affairs. First Nations largely rejected the idea of cultural assimilation into Canadian society. In particular, they spoke out against the enforced enfranchisement provisions of the Indian Act and the extent of the powers that the government exercised over their daily lives. Many groups asked that these "wide and discretionary" powers be vested in First Nations chiefs and councillors on reserves so that they themselves could determine the criteria for band membership and manage their own funds and reserve lands. While the joint committee did not recommend a full dismantling of the Indian Act and its assimilationist policies, it did recommend that unilateral and mandatory elements of the Act be scaled back or revised. The committee also recommended that a Claims Commission be established to hear problems arising from the fulfilment of treaties.

Despite the committee's recommendations, amendments to the Indian Act in 1951 did not bring about sweeping changes to the government's Indian policy, nor did it differ greatly from previous legislation. Contentious elements of the Act such as the involuntary enfranchisement clause were repealed, as were the provisions that determined Indian status. However, the amendments did introduce some changes. For example, sections of the Act banning the potlatch and other traditional ceremonies, as well as a ban on fundraising to pursue land claims, were repealed. Bands were also given more control over the administration of their communities and over the use of band funds and revenues. National pension benefits and other health and welfare benefits were to be extended to First Nations. While the 1951 Act did limit some of the authority of the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development over individual bands, the government continued to exercise considerable powers over the lives of First Nations.

Despite the fact that the Indian Act still limited First Nations' control over their own affairs, by 1960 social and economic conditions on reserve began to improve. That year First Nations were at long last extended the right to vote in federal elections, another recommendation of the 1946 joint committee. First Nations veterans played a big role in this important advance, pointing out that, despite having fought for Canada in two World Wars, they were still deprived the right to vote. Other improvements for First Nations included the provision of better healthcare services in the mid-1950s. With these improvements, the Status Indian population increased rapidly. In addition, many more First Nations children had access to schooling, including secondary and post-secondary education. In general, however, the living conditions of First Nations still fell far short of the standards of other Canadians.

The White Paper

In 1969, the government began to examine a radically new approach to its Indian policy. This approach was based on the view that all Canadians held the same rights regardless of ethnicity, language or history. Arguing that the "special status" of First Nations and Inuit had put them at a disadvantage, and that both of these groups should be fully integrated into Canadian society, the government tabled a policy paper commonly known as the White Paper. This paper called for a repeal of the Indian Act, an end to federal responsibility for First Nations and termination of special status. It also called for the decentralization of Indian affairs to provincial governments, which would then administer services for First Nations. The White Paper further recommended that an equitable way be found to bring an end to treaties. In this way, the government hoped to abolish what it saw as a false separation between First Nations and the rest of Canadian society.

First Nations overwhelmingly rejected the White Paper. The complete lack of consultation with the people who would be directly affected—First Nations themselves—was central to their criticism. It became apparent that while many people regarded the Indian Act as paternalistic and coercive, the Act nevertheless protected special Aboriginal status within Confederation and therefore specific rights. In the face of such strong negative reaction not only from First Nations, but also from the general public, the government withdrew the White Paper in 1971. The government's attempt to change its relationship with First Nations created a new form of Aboriginal nationalism. First Nations leaders from across the country united in new associations and organizations determined to protect and promote their peoples' rights and interests. These organizations proposed their own policy alternatives. The Indian Association of Alberta, for example, argued in a paper entitled Citizens Plus that Aboriginal peoples held rights and benefits that other Canadians did not. Rallying around this concept, First Nations leaders argued that their people were entitled to all the benefits of Canadian citizenship, in addition to special rights deriving from their unique and historical relationship with the Crown.

The federal government slowly began to change its approach and scale back its paternalistic presence in the lives of First Nation, for example, by withdrawing all Indian agents from reserves. The government also began to fund Aboriginal political organizations. This funding allowed these groups to focus on the need for full recognition of their Aboriginal rights and the renegotiation of existing treaties.

Comprehensive Land Claims

As First Nations organizations such as the National Indian Brotherhood (later the Assembly of First Nations) increasingly challenged the government's Indian policy, the courts also began to weigh in on the issue. In the early 1970s, three landmark court decisions brought about an important shift in the recognition of the rights of First Nations in Canada. In Northern Quebec, a proposed hydro-electric project in the James Bay region announced in 1971 became a focal point for Cree and Inuit protests. Arguing that the lands of Northern Quebec were not covered by any existing treaties and that they still held Aboriginal rights over those lands, the Cree Nation and Inuit of Northern Quebec filed for an injunction to block the project until their claim of rights and title was addressed. In an unprecedented decision in Canadian law, in 1973 the Superior Court of Quebec ruled in favour of the Cree and Inuit, deciding that there remained an unfulfilled obligation to resolve Aboriginal title in Northern Quebec.

That same year, the courts once again brought the issue of First Nations claims under public scrutiny. After decades of persistence, the Nisga'a people in British Columbia succeeded in bringing their case before the Supreme Court of Canada. Led by Frank Calder, the Nisga'a argued that Aboriginal title to lands was part of Canadian law. In their 1973 decision in the Calder case, six of the seven Supreme Court justices ruled in favour of the Nisga'a, confirming the legality of Aboriginal title. In a third court case in 1973, the Supreme Court of the Northwest Territories ruled in what has become known as the Paulette Caveat that Canada had not fulfilled its obligations under the terms of Treaties 8 and 11 in the Territories. As such, Aboriginal rights and title could not be fully relinquished to the Crown.

A review of these three monumental court decisions led the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (now Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada or AANDC) to announce its willingness to negotiate land claims based on outstanding Aboriginal title. The Department's new Comprehensive Claims Policy, the aim of which was to settle land claims through a negotiated process, was announced in August 1973. Through this new policy, Aboriginal rights and title would be transferred to the Crown by an agreement that guaranteed defined rights and benefits for the signatories (i.e. land title, fishing and trapping rights, financial compensation and other social and economic benefits). The first agreement under this new policy was with the Cree and Inuit of Northern Quebec. Soon after the 1972 James Bay ruling, the Cree, Inuit and the federal and Quebec governments began negotiations in an attempt to settle Aboriginal claims and allow the hydro-electric development project to resume. Under the final agreement signed in November 1975, the concerned Cree and Inuit groups surrendered their Aboriginal title to about 981,610 square kilometres of the James Bay/Ungava territory in Northern Quebec. In return, these parties were awarded a $225-million settlement, to be paid over 20 years. The Cree and Inuit also received tracts of community lands with exclusive hunting and trapping rights, the establishment of a new system of local government on lands set aside for their use, and First Nations control over their education and health authorities. In addition, the agreement set out measures relating to policing and the administration of justice, continuing federal and provincial benefits, and special social and economic development measures.

Since 1975, the Comprehensive Claims Policy has been modified in response to Aboriginal concerns and positions. Most notably, new options were added in 1986 relating to the transfer of rights and title (as well as a broader scope of rights and other issues). A cap on the number of ongoing negotiations was lifted in 1991.

The negotiation of comprehensive claims is a long and painstaking process, requiring many years to complete. From 1975 to 2009, there were 22 comprehensive claims agreements, commonly known as "modern treaties," concluded across Northern Quebec, the Northwest Territories, Yukon and British Columbia. Two of the most important agreements concluded are the Nunavut and Nisga'a agreements. Signed in 1993, the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement was the first treaty with Inuit in Canada and laid the groundwork for the creation of the Territory of Nunavut on April 1st, 1999. One year earlier in British Columbia, after over a century of claims and 24 years of negotiation, the Nisga'a Agreement was ratified by the Nisga'a, Canada and the province of British Columbia. The Nisga'a Final Agreement of 2000 was the first modern treaty in British Columbia.

Specific Claims Policy

As part of the wider review of how Canada dealt with First Nations claims, AANDC created a companion policy to Comprehensive Claims that addressed claims of a more specific nature. While the idea of addressing specific First Nations claims was first proposed in the 1948 joint committee report, it was not acted upon until 1973. From this point forward the Comprehensive Claims Policy would deal with issues stemming from claims to Aboriginal title, whereas the Specific Claims Policy addressed claims relating to the failure to fulfill any "lawful obligations" flowing from the Indian Act or existing treaties. To accompany the policy, the Office of Native Claims was created to guide claims through the process. However, the claims process proved difficult and cumbersome, leading many First Nations to complain it was ineffective and inefficient. After amendments to the policy in the mid-1980s and again in the early 1990s, the government created the Indian Specific Claims Commission to review AANDC's decisions regarding claims and to make recommendations.

While these changes to the policy did allow for more claims to be addressed, the complexity, volume and diversity of the claims were increasingly difficult to manage. Lengthy delays were common. In 2006, the Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples recommended that the government establish a dedicated fund for the payment of specific claims settlements and an independent body with a mandate and power to resolve specific claims. In response, AANDC invited First Nations organizations to become directly involved in formulating the new Specific Claims Policy. As a result, in 2008 the Specific Claims Tribunal Act created an independent adjudicative tribunal with the authority to make binding decisions on the validity of claims and on compensation.

"Existing Aboriginal and Treaty Rights"

The federal government entered into constitutional discussions with provincial premiers between 1977 and 1981 to reform and repatriate the Constitution. Aboriginal political organizations tried unsuccessfully to get a seat at the negotiations table. When a 1981 constitutional proposal was announced, Aboriginal and treaty rights were excluded. However, after several months of concerted lobbying, First Nations, Inuit and Métis organizations succeeded in having two clauses included in Section 35 of the Constitution, to recognize "existing Aboriginal and treaty rights" and to provide a definition of Aboriginal peoples that included all three groups. At conferences held between 1983 and 1987, attempts were made to define "existing Aboriginal and treaty rights." However, those rights remained undefined because of disagreements between the provinces, Canada and Aboriginal groups. Given this lack of consensus on a clear definition of "existing Aboriginal and treaty rights," responsibility has fallen to the courts to define the extent and scope of these rights and to direct government policies and programs so that they respect these rights and prevent any infringement of them.

Part 6 - Towards a New Relationship

(1982–2008)

Bill C-31

Since the mid-1800s, government policy had dictated that First Nations women automatically lost their Indian "status" if they married non-Aboriginal men. This automatic enfranchisement was entrenched in successive legislation for more than a century. For decades, many First Nations members, especially women, criticized this section of the Indian Act as blatant discrimination. By the 1980s, criticism of this aspect of the Act was widespread throughout Canadian society. Spurred by a series of 1970s court challenges attacking the legality of this loss of status for First Nations women, the government consulted with First Nations leaders across the country on how best to amend the Act.

Parliament passed Bill C-31 in 1985. This amendment to the Indian Act removed discriminatory provisions, eliminated the links between marriage and status, gave individual bands greater control in determining their own membership, and defined two new categories of Indian status. Through this amendment, some 60,000 persons regained their lost status. In addition, Bill C-31 distinguished between band membership and Indian status. While the government would continue to determine status, bands were given complete control over membership lists.

The Oka Crisis and RCAP

The need to deal with the long-standing grievances of First Nations became more urgent following the events at Oka, Quebec, in the summer of 1990. A conflict that would grab near-immediate national attention was sparked on July 11th of that year when the Quebec Provincial Police tried to dismantle a roadblock that had been set up outside Montreal in mid-March by a group of Mohawks from Kanesatake. This First Nation community had erected the roadblock to prevent the nearby town of Oka from expanding a golf course onto sacred Mohawk lands. One police officer was killed during the raid. For 78 days, armed Mohawk warriors faced off against the Quebec Provincial Police, and later the Canadian Armed Forces, before voluntarily withdrawing from their barricade after an agreement was reached between all parties.

Following what became known as the Oka Crisis, First Nations leaders and political commentators across the country debated the impact of the standoff. Supporters of the Mohawk Warriors Society argued that the conflict raised the profile of Aboriginal issues in a way that Aboriginal leaders had been unable to do previously. However, others argued that any gains made were offset by increased racism toward Aboriginal peoples, a loss of credibility for the Aboriginal rights movement and rising militancy among discontented Aboriginal youth.

In an attempt to address the concerns of First Nations leaders, and mere days before the conclusion of the Oka Crisis, the government announced a new agenda to improve its relationship with First Nations. The new measures included progress on land claim settlements, the creation of the Indian Specific Claims Commission, improved living conditions, an improved federal relationship with Aboriginal peoples and a review of the role of Aboriginal peoples in Canadian society. A few months later, in 1991, the government established the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP). The Commission's mandate was to propose specific solutions to issues that had long plagued the relationship between Aboriginal peoples, the government and Canadian society as a whole.

The Commission published its final report in 1996, which included 440 recommendations covering a wide range of Aboriginal issues. The RCAP report is a significant body of work that has been widely used to inform public debate and policy making.

Self-Government

In 1983, in response to First Nations' demands for greater autonomy, the House of Commons established a parliamentary committee (the Penner Committee) to investigate Aboriginal self-government. Following its study, the committee stated in its report that this right was inherent to all First Nations and should be entrenched in the Constitution alongside Aboriginal and treaty rights.

In 1995, the government launched the Inherent Right Policy to negotiate practical arrangements with Aboriginal groups to make a return to self-government a reality. This process involved extensive consultations with Aboriginal leaders at the local, regional and national levels, and took the position that an inherent right of Aboriginal self-government already existed within the Constitution. Accordingly, new self-government agreements would then be partnerships between Aboriginal peoples and the federal government to implement that right. The policy also recognized that no single form of government was applicable to all Aboriginal communities. Self-government arrangements would therefore take many forms based upon the particular historical, cultural, political and economic circumstances of each respective Aboriginal group. Since the introduction of the policy, there have been 17 self-government agreements completed, many of which are part of larger Comprehensive Claims agreements.

National Aboriginal Day

The growing recognition of Aboriginal rights in Canadian law led to calls for greater recognition of the contributions of Aboriginal peoples to Canadian society. Shortly after the adoption of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, the National Indian Brotherhood, the leading body representing First Nations in Canada, called for the creation of a yearly "National Aboriginal Solidarity Day" on June 21st. Pressure for a national day of recognition continued to grow during the following decade as new ways were sought to bridge the divide between Aboriginal peoples and Canadians, especially in the wake of the 1990 Oka Crisis. In 1995, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples recommended the designation of a "National First Peoples Day" as a way to focus attention on the history, achievements and contributions of Aboriginal peoples in Canada. This message was repeated later that year during the Sacred Assembly, a national conference chaired by Elijah Harper, which called for a national holiday to celebrate the contributions of Aboriginal peoples. On June 13, 1996, after considerable consultation with Aboriginal organisations, June 21st was officially declared National Aboriginal Day.

Since its inauguration, National Aboriginal Day has become part of the annual nationwide Celebrate Canada! festivities held from June 21st to July 1st. June 21st was chosen because of the cultural significance of the summer solstice and because many Aboriginal groups mark this day as a time to celebrate their heritage. Setting aside a day for Aboriginal peoples is part of the wider recognition of their important place within the fabric of Canada and the ongoing contributions to Canadian society made by First Nations, Métis and Inuit.

Residential Schools Apology

As the government continued to transfer control of local affairs to individual First Nations, education also began to be decentralized. New education policies began to emerge in the 1970s, with First Nations developing education systems that incorporated both the fundamental elements of a modern curriculum, as well as aspects of their respective traditions, languages and cultures. Special grants for training First Nations teachers, traditional language classes and lessons in First Nations history and culture helped strengthen these new education systems. With these advances, the residential school system increasingly fell out of favour and was slowly phased out. The final residential school, located in Saskatchewan, was closed in 1996.

While First Nations took charge of educating their children, the legacy of the residential school system became increasingly apparent. More and more stories surfaced regarding abuse and mistreatment of children by school administrators and teachers. In 1990, the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs leader Phil Fontaine called on the government and the churches involved with residential schools to acknowledge and address the decades of abuse and mistreatment that occurred at these institutions. In its final report, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples noted the deep and lasting negative impacts this policy had on those who attended the residential schools, as well as their families, communities and cultures. As claims and litigation against the government and churches continued to mount, the first steps toward reconciliation began in the 1990s. The various churches involved in running these institutions were the first to offer their apologies to residential school survivors. In 1998, the government also acknowledged its role in the abuse and mistreatment of Aboriginal students during their time at residential schools.

After nearly a decade of negotiations, in 2007 the Government announced a landmark compensation package (the Common Experience Package) for residential school survivors, worth nearly $2 billion. The settlement included a common experience payment, an independent assessment process, commemoration activities, measures to support healing and the creation of an Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission to act as an independent body and to provide a safe and culturally appropriate place for former students and others affected by the residential school system to share their experiences.

The Government of Canada offered an historic formal apology on June 11, 2008, to all former students of residential schools and asked their forgiveness for the suffering they experienced and for the impact the schools had on Aboriginal cultures, heritage and languages. The apology also made clear the government's commitment to address the legacy of residential schools through continuing measures, including the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.